The following text is from Fr Frank Brennan's presentation 'The Ethical Challenges of Stopping the Boats Upstream and Closing the Camps Downstream: The Politics of Popular Evil and Untrendy Truth' — part of the 'Politics and the Idea of Evil' Series, University of Melbourne Law School, 26 August 2015. Listen to audio recording

'We must not be a party to starting this journey again and putting these people smugglers back into business with the inevitable consequence that there will be a huge loss of life. Because if we do, you can forget about any future Labor Government being remembered for anything else. We will simply be condemned by history.' — Richard Marles, ALP National Conference 2015

If you want to form government in Australia and if you want to lead the Australian people to be more generous, making more places available for refugees to resettle permanently in Australia, you first have to stop the boats. If you want to restore some equity to the means of choosing only some tens of thousands of refugees per annum for permanent residence in Australia from the tens of millions of people displaced in the world, you need to secure the borders. The untrendy truth is that not all asylum seekers have the right to enter Australia but that those who are in direct flight from persecution whether that be in Sri Lanka or Indonesia do, and that it is possible fairly readily (and even on the high seas) to draw a distinction between those in direct flight and those engaged in secondary movement understandably dissatisfied with the level of protection and the transparency of processing in transit countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia. The popular evil is that political parties are rewarded for being tough on all asylum seekers and for excluding them from Australia unless they have first gained admission by invitation on receipt of a visa even if the visa be obtained by partial admission of the facts.

When interviewed in 2003 about his 1973 article on 'Dirty Hands', Michael Walzer said, 'Rules are rules, and exceptions are exceptions. I want political leaders to accept the rule, to understand the reasons, even to internalize it. I also want them to be smart enough to know when to break it. And finally, because they believe in the rule, I want them to feel guilty about breaking it — which is the only guarantee they can offer us that they won't break it too often.' Our host Raimond Gaita has long been critical of Walzer's approach to this vexed philosophical issue. But even Rai has conceded that 'Governments will do evil to protect their peoples, and their peoples will, mostly, consent to it. They will look upon those who do not as strangers in their midst.' Explaining why those who refuse to do evil are 'not one of us', or perhaps more simply and pragmatically not ever likely to govern us, Gaita says, 'The acknowledgement in advance that we will do evil is a condition of political communality as such. It is a condition of the sober acknowledgement of one's political persona. Acknowledgement in advance that we will do evil and the absence of justification for doing it (because for example it is the lesser of two evils) distinguishes this from a moral dilemma'. Ethical behaviour requires a consideration of moral injunctions, political imperatives, and the rule of law. As Gaita says, 'The national interest is not an ethical-free zone.' But when it comes to the national interest, individual moral injunctions may be confined by political imperatives. Because of the political imperatives, it is no longer a moral dilemma whether to stop the boats. Unless committed to stopping the boats, our politicians will never be elected to government and they will never be in a position to make our asylum policy more benign. Minor parties, NGOs and faith communities will continue to espouse open borders but they have no expectation that their moral prescriptions will ever form the basis for future laws and policies. Scholars such as Matthew Gibney espousing 'the humanitarian principle' have traced how governments have the role of leading the community in developing greater sympathy for the admission of more asylum seekers and that this can be done only if the public is first assured that their borders are secure. Gibney rightly contrasts the partial and the impartial view, discounting each of them as inadequate to the task. The partial view 'brings to the fore the claims of citizens to maintain self-determining political communities which sustain their collective way of life', while the impartial view 'highlights the claims of human beings in general — and refugees in particular — to equal consideration'. The humanitarian principle which straddles between the partial and impartial views not only requires respect for the principle of non-refoulement, but also requires wealthy secure states to boost their efforts to resettle refugees and to contribute to better community acceptance and international co-operation in fostering 'a more favourable national and international environment for refugees'

All major political parties in Australia are now committed to stopping the boats. The majority of voters want the boats stopped. What are the rules? What are the exceptions? What are the circumstances in which our leaders are justified in breaking the rules?

It is time to concede that none of us has a right to enter another country and that all of us have the obligation not to return anyone presenting at our border to a situation of persecution, torture, or cruel punishment. None of us would want more realistic and more decent options in these most toxic of times to be forfeited simply because there is a new emerging fundamentalism being espoused by NGOs and some international lawyers. There is of course no way that the Europeans in the present crisis in the Meidterranean could be returning asylum seekers to Libya which is a failed state. I doubt the possibility of the EU negotiating appropriate returns of asylum seekers to Libya in the foreseeable future. But I continue to entertain the hope that Australia can negotiate appropriate returns to transit countries such as Indonesia for Iraqis, Afghans and Iranians and India for Tamils, so that Australia might then decently extend the hand of welcome to more of the world's 59.5 million displaced persons. For the moment, Australia is failing to strike the right balance between human rights and the national interest. It is stopping the boats indecently (or at least non-transparently), violating the human dignity of those being held in highly unsatisfactory conditions in Papua New Guinea and on Nauru and failing to ensure appropriate safeguards are in place for the return of asylum seekers to Indonesia.

For as long as international lawyers claim there is no possibility of a legally negotiated regional agreement for safe returns because they argue that asylum seekers have a right of entry to Australia to seek asylum, the Australian government, the Australian parliament, and the Australian courts will maintain, with impunity but with the occasional expression of outrage from international lawyers, a regime of returns insufficiently scrutinised for human rights compliance. I accept that the boats headed for Australia will continue to be stopped (no matter which political party is in power), but that they should be stopped decently and in compliance with the legal regime enunciated by the European Union which has to deal with a far more pressing issue but subject to the more searching supervision of the European Court of Human Rights and of the European Parliament which has greater sensitivity to the human rights of asylum seekers than do their more pragmatic Australian colleagues.

The untrendy truth is that asylum seekers who make it to Australia are entitled to proper processing, protection and durable solutions. Another untrendy truth is that an asylum seeker has no right to enter Australia unless they are still in direct flight from persecution. The things still being done on Nauru and on Manus Island in our name are a popular evil. In the long term the boats need to be stopped decently. In the short term, what evil would be justified to achieve that outcome?

I have long been challenged by George Orwell's famous remark: 'Those who "abjure" violence can do so only because others are committing violence on their behalf.' We who live behind secure borders on an island nation continent where we elect only governments committed to stopping the boats by hook or by crook have to accept that the peace, prosperity and security we enjoy is bought at a price paid by others who are cheated peace, prosperity and security. I have been particularly stimulated by Nigel Biggar's writings on war and peace because he thinks that many of us Christians (and I am probably one of those in his sights) are too pacifist in our approach to moral questions about war. Biggar describes the dilemma which confronts each of us in a world marred by violence and injustice:

This is the dilemma: on the one hand going to war causes terrible evils, but on the other hand not going to war permits them. Whichever horn one chooses to sit on, the sitting should not be comfortable. Allowing evils to happen is not necessarily innocent, any more than causing them is necessarily culpable. Omission and commission are equally obliged to give an account of themselves. Both stand in need of moral justification.

Similarly with stopping the boats and securing the borders while at the same time maintaining a strict quota on the annual apportionment of places for permanent resettlement. Those of us who espouse open borders encourage people to make dangerous journeys but we also preference those who have the resources and the initiative to present on our doorstep over against those who have neither the resources nor the initiative to take the journey from an African refugee camp to Christmas Island. In 2013, UNHCR received 8,300 new applications in Indonesia for asylum. In 2013, there were 3,206 registered refugees and 7,110 asylum seekers on the books of UNHCR. In 2014, the number of new asylum claims in Indonesia dropped sharply to 5,700. There were 4270 registered refugees (an increase of a thousand, presumably in part because Australia is now not taking any refugees from Indonesia registered after June 2014) and 6916 asylum seekers on the books of UNHCR. It would seem that the Australian government policies are having an effect in dissuading asylum seekers from heading to Indonesia in the first place, let alone then attempting the boat journey on to Australia.

At the ALP party conference, Richard Marles Shadow Minister For Immigration And Border Protection on 25 July 2015 said:

The particular issue at hand is the journey from Java to Christmas Island. The vast majority of those who undertake this journey are genuine refugees. But this journey of itself is not a flight from persecution. No one is fleeing persecution in Indonesia.

What characterises this journey are people smugglers. And we are not talking about Oscar Schindlers here. We are talking about vicious criminal networks, who are making huge profits, by preying on the world's most vulnerable people with the result that hundreds, ultimately thousands died.

And by in large, these people smugglers are now out of business, some driving taxis in Jakarta. This is not conjecture, we have certain knowledge.

And so we must not be a party to starting this journey again and putting these people smugglers back into business with the inevitable consequence that there will be a huge loss of life. Because if we do, you can forget about any future Labor Government being remembered for anything else. We will simply be condemned by history.

Those of us who live in prosperous, secure countries need to answer the questions: Who has a right to enter my country? What are the preconditions for my government being able decently and fairly to deny a right of entry to someone seeking entry to my country? In August 2014 I spent a week down on the Mexico-US border visiting the KINO Border Initiative at Nogales. I visited the spot at the border fence where Cardinal O'Malley had celebrated mass reaching through the steel girders to give communion to persons on the other side of the border. I heard some of the stories about the desperate attempts of border crossers, many of whom were children fleeing impossibly lawless situations back home heading for the safety of their dreams with relatives already resident in the US. Fr Sean Carroll SJ, Director of KINO, told me that the number of people coming to the border has tapered off, in part because of Mexico's southern border plan with Mexican state officials running stricter checkpoints, pulling people off trains and beating them up, and in part because of police activities in countries like Honduras making it more difficult for children to escape. The Mexican southern border plan could not be implemented without US funding. The cumulative effect is 'the externalization of the US border'. In effect, the border has been moved south, out of sight and out of mind.

Australia is a nation state first founded on Aboriginal dispossession. It is now a very multi-cultural society. It is an island nation continent. It is a nation refounded on migration, and since World War II and the subsequent abolition of the White Australia Policy, on migration from every country on earth. Australia has a generous, ordered, well policed immigration policy. Australia has been particularly generous receiving refugees fleeing conflicts across the globe, though usually those refugees have been selected by the Australian government issuing visas to those refugees chosen from a large pool. Other refugees have come to Australia on business or tourist visas, then claiming asylum on arrival in Australia. Some refugees have arrived by boat, uninvited and unscreened. Australian Governments of both political persuasions (Liberal and Labor) have expressed a strong preference for the maintenance of an orderly migration program including the reception of an annual quota of refugees chosen from abroad, usually in consultation with the UNHCR.

Ever since the first boatloads of Vietnamese asylum seekers arrived in Darwin in 1976, Australian Governments of both political persuasions have had a strong commitment to stopping the boats while at the same time maintaining programs for the resettlement of proven refugees. The Australian public tends to reward political parties which can deliver on the election pledge to stop the boats.

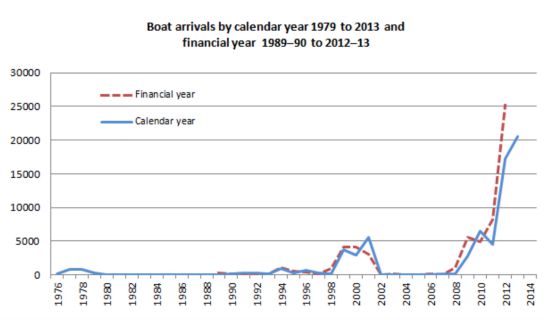

Ten years ago, I worked on a second edition of my book Tampering with Asylum. That book and my advocacy made a modest contribution, along with the efforts of many others, to convincing the newly elected Rudd Labor government to wind back the so-called Pacific Solution instituted by the Howard Government in 2001 when boatloads of asylum seekers started arriving in Australian territorial waters from Indonesia. This time these boat people did not originate from Southeast Asia. These asylum seekers came mainly from faraway Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran. They had not fled Indonesia fearing persecution there, but they had continued their global journey from there towards Australia seeking protection, recognition as refugees, and a new life. The measures instituted by the Howard government in 2001 contributed to the changed circumstances which did stop the boats. The reforms instituted by the Rudd government in 2008 contributed to the changed circumstances which resulted in the boats coming in numbers not previously experienced. Commentators like myself were proved wrong. In Tampering with Asylum, I had provided a checklist of legal and policy reforms, most of which were enacted by the Rudd government. I had written: 'There is no reason to think that our onshore caseload will increase exponentially given the improved regional arrangements, the virtual offshore border and the tighter controls within Australian territory.' During seven years of the Rudd and Gillard Labor governments, over 50,000 asylum seekers arrived by boat. There were at least 1,200 lives lost at sea. By the time the Rudd government was voted out of office, government intelligence sources were advising that the number could rise to 60,000 per annum. For a country of nearly 24 million people with an annual migration intake of 190,000 for skilled migrants and family reunion, with an additional 13,750 places available for humanitarian cases, this was a projected arrival rate which would skew the composition of the migration program very significantly, removing all prospect of offering places to offshore refugees or other persons in desperate humanitarian need. Prior to this influx, the number of boat people reaching Australia was usually consistent with Michael Walzer's classification of the numbers being 'small and the people easily absorbed', thus creating the duty to grant asylum. The 2013 numbers had reached an historic high warranting the invocation of Walzer's caution:

The call 'Give me ... your huddled masses yearning to breathe free' is generous and noble; actually to take in large numbers of refugees is often morally necessary; but the right to restrain the flow remains a feature of communal self-determination. The principle of mutual aid can only modify and not transform admissions policies rooted in a particular community's understanding of itself.

At its most generous in recent years, Australia has provided 20,000 humanitarian places a year. Community groups supportive of refugees have asked government to increase the humanitarian quota to 25,000 per year 'or no less than 15 per cent of the annual migration intake, whichever is higher'. In 2012, the Expert Panel on Asylum Seekers recommended that Australia increase its humanitarian intake to 27,000 places per annum by 2017. There is a modest Community Proposal Project in place allowing community groups to sponsor up to 500 refugees a year who would not otherwise be chosen to come to Australia. But 500 places are then deducted from the existing annual refugee quota and the visa fees are prohibitive for the most recently arrived refugee groups.

The present humanitarian caseload has been cut by the Abbott government from 20,000 places to a mean 13,750 places. Those asylum seekers arriving without a visa are eligible only for a temporary protection visa should they establish their refugee claim. There are more than 30,000 onshore unvisaed asylum seekers who arrived by boat during the years of the Labor government whose applications for onshore refugee status are still to be processed.

Most of us are citizens of a nation state. It is the nation state primarily which has the duty to protect our human rights. The governments of many nation states have voluntarily ratified an increasing raft of international human rights instruments which in part limit the untrammelled sovereignty of the nation state, providing a framework for enhanced protection of the human rights of all persons within the jurisdiction of the nation state. An international legal order which accords ongoing recognition to national sovereignty is sustainable only if there be an international legal regime ensuring the protection of the human rights of refugees - those whose rights are most flagrantly violated by the government of their own nation state, those who cannot expect any protection from their own government. At the very least, the quid pro quo for national sovereignty and the security of national borders is the international community's commitment to protect those who are refugees — those who have fled their home country fearing persecution and abuse of their human rights by their own government. Nation states are entitled to secure their borders but they must not expel their own nationals nor deny their own nationals entry to their country. But what are the moral and legal considerations when it comes to those who are not nationals seeking admission, especially those seeking asylum? Does the asylum seeker have a right to enter? If not, what is the duty of the nation state to the asylum seeker presenting at the border?

Joseph Carens, professor of political science at the University of Toronto, has been a lifetime scholar of the ethics of immigration. In 2013 he published a book with that very title, The Ethics of Immigration, concluding that 'the conventional view that states are morally entitled to exercise discretionary control over immigration' is wrong. He argues that 'our deepest moral principles require a commitment to open borders (with modest qualifications) in a world where inequality between states is much reduced'. He thinks that our inherited citizenship in rich states like the United States, his home country Canada, and Australia functions as 'a form of illegitimate privilege'. He thinks his ideal would not work the havoc you might imagine if there were greater equality between states as there would then be less incentive for people to leave the state where they grew up and established their roots. But absent that equality, what is to be done?

Carens expresses the fear that there is now 'a deep conflict between what morality requires of democratic states with respect to the admission of refugees and what democratic states and their existing populations see as their interests.' He concedes that the principle of non-refoulement might create disproportionate burdens for rich democratic states all of which design systems for excluding unwelcome applicants. He notes that 'refugees might reasonably say to themselves that if they have to start life over somewhere new it would be better to do so in a place with more long-term opportunities for themselves and especially for their children. Many refugees would not have the resources to act upon this sort of calculation, but the principle of non-refoulement creates incentives for refugees to seek asylum in a rich democratic state rather than somewhere else'. If rich democratic states were to have an open border policy, no doubt this would become a problem. There is no prospect of any political party which advocates an open border policy being elected to government in any of these countries. There is no prospect of the Congress or parliament in any of these countries legislating for open borders. Given that the rich democratic states will provide only a limited number of spaces for refugees outside their jurisdiction, and given that the limited number of spaces will only ever be a miniscule percentage of those who are bona fide refugees in our troubled world, how should those lucky persons in the lottery of resettlement in a rich democratic country be chosen? Carens speaks of the 'moral wrong involved in the use of techniques of exclusion to keep the numbers within bounds' describing 'visa controls, carrier sanctions, and the other techniques of exclusion' as 'indiscriminate mechanisms'. His main suggestion for such democratic countries avoiding the need for the use of these morally questionable techniques is to break the link between claim and place, noting:

People have incentives to seek asylum in places where they will be better off economically than they were at home, regardless of the strength of their refugee claims. If there were no connection between the place where one requests asylum and the place where one receives protection, however, these incentives would disappear.

Of late, Australian governments have experimented with this approach, denying asylum seekers arriving by boat any prospect of resettlement in Australia, but offering them, on proof of refugee status, resettlement in less desirable countries like Nauru, Papua New Guinea and Cambodia. Most community leaders and advocates regard these experiments as costly, inhumane failures.

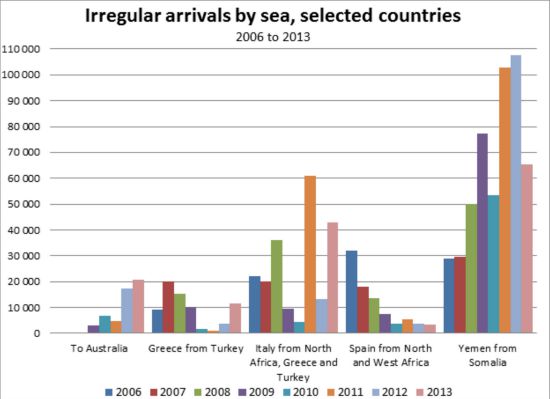

On World Refugee Day 2015, reported 'By end-2014, 59.5 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or human rights violations. This is 8.3 million persons more than the year before (51.2 million) and the highest annual increase in a single year.' In 2014, 866,000 persons applied for asylum in those 44 industrialised countries which provide UNHCR with statistics. That was a 45 per cent increase on the previous year. It was the second highest number of annual applications on record. During 2014, more than 218,000 people seeking asylum crossed the Mediterranean Sea seeking access to Europe. That was three times the previous known high of about 70,000 in 2011 during the 'Arab Spring'. Already this year more than 300,000 have crossed the Mediterranean seeking asylum. The US received 121,200 asylum claims in 2014, an increase of 44 per cent on the previous year. During the year, UNHCR submitted 103,800 refugees to States for resettlement. According to government statistics, 26 countries admitted 105,200 refugees for resettlement during 2014 (with or without UNHCR's assistance).

What is to be done when asylum seekers come knocking on our doors in such numbers? Is there a right of entry? If not, what is our obligation to the asylum seeker presenting to officials of our governments whether at our embassies, on the high seas, within our territorial waters, or on our shores? Are we entitled to stipulate a gradation of obligation and a gradation of judicial-type processing and review depending on where an asylum seeker presents? Are we entitled to set up an ante-chamber with an offshore entry door at some considerable distance from our border?

Hiroshi Motomura, the author of the highly acclaimed Americans in Waiting has recently published Immigration Outside the Law. In part he is investigating how we might extend the rule of law to immigration and border protection, applying the rule of law at the border, inside the border, and after the border crossing. To what extent are our governments justified in excluding the rule of law other than the minimal agreed international safeguards beyond the border? And what are those safeguards? Motomura's main focus is not on asylum seekers outside or at the border but on the 15 million long term residents inside the USA border who are noncitizens without lawful status. He espouses 'a nation with borders, but also a nation committed to a sense of equality and human dignity' - where 'humanitarian obligations recognized by international conventions can override immigration violations'. These ideals have relevance to government behaviour outside the border as well as inside and at the border. Admittedly, the rule of law is more readily applied or invoked when those seeking it already have strong links to the citizenry or a legitimate expectation that they soon will be citizens.

Mine, I hope, is a principled and pragmatic approach. I invite you to imagine the scene on Saturday, 20 July 2013. I had been in Myanmar out of reach for a week. On the previous afternoon, the Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd announced his Papua New Guinea Solution to the increased flow of boat people heading to Australia seeking asylum. He declared that all boat people headed for Australia would be moved to PNG for processing and ultimate resettlement with the guarantee that they would never reach Australia. Landing in Sydney, my first telephone conversation was with Paris Aristotle, a refugee advocate who has been an adviser to Australian governments of all political persuasions. Knowing that I was a friend of Rudd, Paris said to me, 'Frank, you are never to leave the country again without permission.' I then spent a few hours writing a critical assessment of the government proposal publishing it immediately on the internet. In part this is what I wrote:

Since the Houston Panel reported almost a year ago, it has been very clear that all major political parties in Australia are of the unshakeable view that there is a world of difference between an asylum seeker in direct flight from persecution seeking a transparent determination of their refugee claim which if successful will result in the grant of temporary protection, and an asylum seeker prepared to risk life and fortune to engage a people smuggler to obtain not just temporary protection but permanent resettlement in first world Australia. With the rapid increase in the number of boat people arriving from Indonesia this past two years and the corresponding increase in deaths at sea, I have been one refugee advocate prepared to concede this distinction, though claiming that the line is often difficult to draw. The line could be drawn more compellingly if there was a basic level of processing and protection in Indonesia, Malaysia and throughout the region which could be endorsed by the UNHCR. That is a work which would require a lot of painstaking high level diplomacy. And it definitely cannot be done before the 2013 Australian election. I respect those refugee advocates who think such a regional agreement would never be possible. But I still think it's worth a try. All decent Australians remain open to providing protection to fair dinkum asylum seekers in direct flight from persecution to our shores. The majority of voters think that the people smugglers and some of their clients are having a lend of us. The mantra of processing and permanently resettling all asylum seekers will not have any appeal to any major political party in Australia for a very long time to come.

Some refugee advocates in the past gave cautious approval to the Gillard Government's Malaysia Solution. That arrangement was based on the premise that it would stop the boats because no one would risk life and fortune to be amongst the first 800 to arrive in Australia only to be moved to Malaysia to join the other 100,000 people of concern to UNHCR. The Malaysia deal would not have resulted in any significant improvement to the upstream conditions for asylum seekers in Indonesia. It was simply a means of trying to stem the boat flow. Malaysia never made sense to me because no one could say what would be done with unaccompanied minors and other particularly vulnerable individuals. If kids without parents were included in the 800, the arrangement would be unprincipled; if not, it would be unworkable because the next lot of boats would have been full of kids.

In the short term, no government will stop the boats unless there is a clear message sent to people smugglers and people waiting in Indonesia to board boats. But that message must propose a solution which is both workable and basically fair, maintaining the letter and spirit of the Convention and Australian law.

I then boarded another plane and flew to Brisbane for a social event at the Prime Minister's home. Being ushered into the Prime Ministerial study, I was able to say that I had already published my view on the new policy. Rudd and I, being friends, agreed that we had our distinctive tasks and duties to perform.

Ever since, I have continued asking what are the ethical and legal preconditions for Australia being able to turn back the boats? Many refugee advocates continue to be upset with me for conceding that any such discussion is theoretically possible, let alone practically necessary. Prime Minister Rudd issued a challenge to all refugee advocates and social justice groups when he appeared on national television in the lead up to the 2013 Australian election saying:

I think you heard a people smuggler interviewed by a media outlet the other day say that this was a fundamental assault on their business model. Well, that's a pretty gruesome way for him to put that, but the bottom line is this, I challenge anyone else looking at this policy challenge for Australia to deliver a credible alternative policy.

The challenge that I put out to anyone who asks that we should consider a different approach is this: what would you do to stop thousands of people, including children, drowning offshore, other than undertake a policy direction like this? What is the alternative answer?

There is much confusion about the ethical and legal considerations which apply when asylum seekers present at the borders of first world countries. For example, in what, if any, circumstances does or ought an asylum seeker have the right to enter a country not her own in order to seek protection? To be blunt, no asylum seeker should be refouled or sent back to the country where they claim to face persecution unless their claim has been assessed and found wanting; while waiting, no asylum seeker has a right to enter any particular country. In the event that an asylum seeker unlawfully gains access to a country, they should not be penalised for such an unlawful entry or presence provided only that they came in direct flight from the alleged persecution. All lawyers would agree with these blunt propositions. Some, especially those schooled in international law, would go further. They would point not just to a country's ratification of the 1951 Refugees Convention. They would claim that those countries which have ratified the Convention against Torture and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights cannot refoule an asylum seeker until there has been a determination of any claim that they face torture or 'cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment'. Some of these lawyers would then take the next leap in human rights protection to assert that all persons have a right to enter any state of their choice provided only they claim to face the risk of persecution, torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment back home. They translate the right not to be refouled into a right of entry to any state unless and until the state determines that there is no real risk of any of these adverse outcomes either back home or in a transit country. Either the state is able to determine all such claims at the border or else the state must grant entry at least for the purpose of a complete human rights assessment.

Much to the consternation of some refugee advocates, the Australian Government continues to claim: 'International law recognises that people at risk of persecution have a legal right to flee their country and seek refuge elsewhere, but does not give them a right to enter a country of which they are not a national. Nor do people at risk of persecution have a right to choose their preferred country of protection.'

Australian governments (of both political persuasions, Labor and Liberal) have long held the defensible view:

The condition that refugees must be 'coming directly' from a territory where they are threatened with persecution constitutes a real limit on the obligation of States to exempt illegal entrants from penalty. In the Australian Government's view, a person in respect of whom Australia owes protection will fall outside the scope of Article 31(1) if he or she spent more than a short period of time in a third country whilst travelling between the country of persecution and Australia, and settled there in safety or was otherwise accorded protection, or there was no good reason why they could not have sought and obtained protection there.

The right to 'seek and enjoy asylum' in the international instruments must be understood as purely permissive. As noted by Justice Gummow of the Australian High Court:

[The] right 'to seek' asylum [in the UDHR] was not accompanied by any assurance that the quest would be successful. A deliberate choice was made not to make a significant innovation in international law which would have amounted to a limitation upon the absolute right of member States to regulate immigration by conferring privileges upon individuals ... Nor was the matter taken any further by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ... Article 12 of the ICCPR stipulates freedom to leave any country and forbids arbitrary deprivation of the right to enter one's own country; but the ICCPR does not provide for any right of entry to seek asylum and the omission was deliberate.

Nation states which are signatories to these international instruments are rightly obliged not to expel peremptorily those persons arriving on their shores, legally or illegally, in direct flight from persecution. That is the limit of the legal obligation. So there may in the future be circumstances in which Australia would be entitled to return safely to Indonesia persons who, when departing Indonesia for Australia, were no longer in direct flight but rather were engaged in secondary movement seeking a more favourable refugee status outcome or a more benign migration outcome. We Australians could credibly draw this distinction if we co-operated more closely with Indonesia providing basic protection and fair processing for asylum seekers there. Until we do that, there is no way of decently stopping the boats.

I am a strong critic, and always have been, of Australian measures such as long term detention, offshore processing such as that practiced in Nauru and PNG, and cheque book solutions to resettlement, like the Cambodia solution. Since 2013, knowing there is strong bipartisan support for a return to Pacific solution type options in the Australian Parliament, I have wanted to investigate if ever it might be possible to turn back boats to Indonesia decently, fairly and legally.

Highly respected international lawyers, including professors like Guy Goodwin Gill and Jane McAdam, seem to be answering, 'No, it could NEVER be legal.' If that be so, it is not an option, and we will be left with non-transparent returns (which suit both Australia AND Indonesia) and punitive, deterrent measures post-entry to Australia and in places like Nauru and PNG.

My quandary has been this. Indonesia is a signatory to the ICCPR and CAT. It makes regular reports to the requisite UN bodies. In 2008, the Committee Against Torture wanted assurances in Indonesian domestic law that refoulement would never be able to occur. But there was no evidence in the report about any particular case or alleged violation. In August 2013, the Human Rights Committee published its most recent concluding observations on Indonesia. This quite detailed report made no mention of any concerns relating to refoulement — either under ICCPR or CAT. The question arises: Given that Indonesia is a signatory to CAT and ICCPR, given that Indonesia complies with the reporting provisions of CAT and ICCPR, given that there are no confirmed reports of Indonesia wrongly refouling persons returned from Australia, and given that Indonesia is NOT and is not likely to be a signatory to the Refugee Convention, could the conditions ever be fulfilled which would warrant Australia returning asylum seekers to Indonesia provided only that Australia is satisfied that the asylum seekers are not in direct flight from persecution IN Indonesia, and provided Australia is satisfied that the returnees will not face the real risk of torture, cruel or degrading treatment in Indonesia?

It is the height of legal formalism to posit that one could never entertain the notion of setting preconditions for such returns (such as UNHCR supervised processing and IOM administered accommodation and services etc) only because Indonesia is not a signatory to the Refugee Convention. It is one thing to have credible evidence of wrongful refoulement from Indonesia prior to determination of claims; it is another to rule out ab initio the possibility of safe returns to Indonesia. If you do the latter, how could you ever even be satisfied that Indonesia's accession to the Refugee Convention would ever justify returns? The reductio ad absurdum of Goodwin Gill's position is that Australia could NEVER return anyone to Indonesia regardless of what instruments it had signed and regardless of what international reporting it had undertaken.

Many of the Australian debates now come down to advocates alleging that Australian policy is contrary to the 'spirit' of the Refugee Convention, with government responding that its policy is consistent with the 'letter' of the Convention. Compliance with the 'letter' does not make a policy right or decent. There is often a need for more robust moral argument and also more finely honed constitutional and statutory construction arguments to counter what is being proposed.

In Europe, the focus has been on boats coming across the Mediterranean Sea. The European Court of Human Rights has developed a more human-rights-friendly approach to the reception of asylum seekers. The European Court of Human Rights became apprised of the EU practices in the Mediterranean in the 2012 case Hirsi v Italy. The applicants in that case were eleven Somali nationals and thirteen Eritrean nationals who were part of a group of about two hundred individuals who left Libya aboard three vessels with the aim of reaching the Italian coast. On 6 May 2009, when the vessels were 35 nautical miles south of the island of Lampedusa, they were intercepted by three ships from the Italian Revenue Police and the Coastguard. The occupants of the intercepted vessels were transferred onto Italian military ships and returned to Tripoli. On arrival in the Port of Tripoli, the migrants were handed over to the Libyan authorities. According to the applicants' version of events, they objected to being handed over to the Libyan authorities but were forced to leave the Italian ships. At a press conference held on 7 May 2009 the Italian Minister of the Interior stated that the operation to intercept the vessels on the high seas and to push the migrants back to Libya was the consequence of the entry into force on 4 February 2009 of bilateral agreements concluded with Libya, and which represented an important turning point in the fight against clandestine immigration. The applicants complained that they had been exposed to the risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment in Libya and in their respective countries of origin as a result of having been returned. They relied on Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights which provides: 'No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.'

The Court said:

The Court has already had occasion to note that the States which form the external borders of the European Union are currently experiencing considerable difficulties in coping with the increasing influx of migrants and asylum seekers. It does not underestimate the burden and pressure this situation places on the States concerned, which are all the greater in the present context of economic crisis. It is particularly aware of the difficulties related to the phenomenon of migration by sea, involving for States additional complications in controlling the borders in southern Europe. However, having regard to the absolute character of the rights secured by Article 3, that cannot absolve a State of its obligations under that provision. The Court reiterates that protection against the treatment prohibited by Article 3 imposes on States the obligation not to remove any person who, in the receiving country, would run the real risk of being subjected to such treatment.

The Court ruled unanimously that the applicants were within the jurisdiction of Italy for the purposes of Article 1 of the Convention; that there had been a violation of Article 3 of the Convention on account of the fact that the applicants were exposed to the risk of being subjected to ill-treatment in Libya; and that there had been a violation of Article 3 of the Convention on account of the fact that the applicants were exposed to the risk of being repatriated to Somalia and Eritrea.

Australia does not have a Human Rights Act, and it is not accountable to any outside judicial body like Strasbourg. This may help to account for Australia's less nuanced approach to 'stopping the boats'. In Australia, the Executive finds itself freer from judicial constraint. Australia is presently quite sterile ground for international lawyers agitating the rights of asylum seekers. Not only has the High Court made clear that there is little room for the application of international law when interpreting tight statutory provisions aimed at enhancing border protection. The Australian Parliament has now legislated a string of new statutory provisions specifying that the exercise of various border protection powers is not invalid:

(a) because of a failure to consider Australia's international obligations, or the international obligations or domestic law of any other country; or

(b) because of a defective consideration of Australia's international obligations, or the international obligations or domestic law of any other country; or

(c) because the exercise of the power is inconsistent with Australia's international obligations.

Permit me to be so bold, being a Jesuit and a lawyer, to suggest that public moral argument posited on religious conviction as well as domestic judicial review are two necessary, additional devices for reining in the executive government responding to populist sentiment to secure the borders and stop the boats. It is the judicial method which permits fine consideration of the claims of those who present at our borders, helping to counter the more broad stroke governmental decisions to punish those who present at our borders in order to send a message to other intending asylum seekers and to give a preference to those asylum seekers chosen by government rather than those who self-select by presenting themselves at the border. It is the moral argument (whether religious or not) which augments the secular liberal approach within the nation state. The secular liberal finds it hard to formulate an argument for universal care extending beyond the injunction for government to care for their own citizens maintaining the security of their borders. At the very least, the secular liberal should concede the assistance which might be obtained from the religious practitioners who profess the dignity of all human persons, and not just those holding passports for nation states living in peace and with economic security.

Lampedusa continues to be a beacon for asylum seekers fleeing desperate situations in Africa seeking admission into the EU. Lampedusa is a lightning rod for European concerns about the security of borders in an increasingly globalized world where people as well as capital flow across porous borders. That's why Pope Francis went there on his first official papal visit outside Rome. At Lampedusa on 8 July 2013, Pope Francis said:

'Where is your brother?' Who is responsible for this blood? In Spanish literature we have a comedy of Lope de Vega which tells how the people of the town of Fuente Ovejuna kill their governor because he is a tyrant. They do it in such a way that no one knows who the actual killer is. So when the royal judge asks: 'Who killed the governor?', they all reply: 'Fuente Ovejuna, sir'. Everybody and nobody! Today too, the question has to be asked: Who is responsible for the blood of these brothers and sisters of ours? Nobody! That is our answer: It isn't me; I don't have anything to do with it; it must be someone else, but certainly not me. Yet God is asking each of us: 'Where is the blood of your brother which cries out to me?' Today no one in our world feels responsible; we have lost a sense of responsibility for our brothers and sisters. We have fallen into the hypocrisy of the priest and the levite whom Jesus described in the parable of the Good Samaritan: we see our brother half dead on the side of the road, and perhaps we say to ourselves: 'poor soul…!', and then go on our way. It's not our responsibility, and with that we feel reassured, assuaged. The culture of comfort, which makes us think only of ourselves, makes us insensitive to the cries of other people, makes us live in soap bubbles which, however lovely, are insubstantial; they offer a fleeting and empty illusion which results in indifference to others; indeed, it even leads to the globalization of indifference. In this globalized world, we have fallen into globalized indifference. We have become used to the suffering of others: it doesn't affect me; it doesn't concern me; it's none of my business!

Here we can think of Manzoni's character — 'the Unnamed'. The globalization of indifference makes us all 'unnamed', responsible, yet nameless and faceless.

It is all very well for the Pope to say these things. But who is listening? And even if they are listening, who is taking any notice? The Pope's intervention and the innate moral sense of the Italian community that there had to be a more decent way of dealing with prospective migrants drowning in the Mediterranean contributed to the Italian Government's decision to establish the short lived and very expensive Mare Nostrum operation.

In Australia, some refugee advocates have been pining for the past leadership of the now deceased Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser. Whitlam was prime minister at the end of the Vietnam War. He was succeeded by Fraser in December 1975. Each of them was concerned by the prospect of large numbers of Vietnamese refugees arriving in Australia by boat and without visas. Fraser led the nation in espousing the need for Australians to be generous in their response to Vietnamese boat people scattered to all corners of South East Asia. We need to remember however that both political parties were equally committed to stopping the boats coming directly uninvited into Darwin Harbour. Initially with the fall of South Vietnam, Australian politicians and civil servants were very wary about receiving large numbers of refugees from Vietnam. A joint parliamentary committee was unanimously of the view when reporting in 1976 that prior to the evacuation of the Australian embassy in Saigon in 1975 there was 'deliberate delay in order to minimise the number of refugees with which Australia would have to concern itself'. Politicians from both sides of the aisle stated, 'As unpalatable as it may be, we are forced to conclude that the [Whitlam] Government acted reluctantly and, as expressed by one witness, in order to placate an increasingly suspicious Australian public.'

As prime minister, Fraser gave great leadership in the Australian community cultivating public acceptance of the idea that Australia would play its part in receiving a significant number of Vietnamese refugees chosen by Australian government officials from camps in other South East Asian countries like Thailand. Eventually an orderly departure program was negotiated with the Vietnamese government. Despite the small number of boat arrivals, there were members of parliament on both sides of the political aisle in Australia expressing concerns about 'queue jumpers' and those falsely claiming to be refugees while seeking a better life. Both Whitlam and Fraser, like all their political successors, expressed concerns about boat people arriving without visas and without prior selection by Australian officials. In May 1977, Fraser's minister for Immigration, Michael MacKellar set out Australia's first comprehensive refugee policy insisting: 'The decision to accept refugees must always remain with the Government of Australia.' He announced, 'There will be a regular intake of Indo-Chinese refugees from Thailand and nearby areas at a level consistent with our capacity as a community to resettle them. In this operation we shall be relying greatly on the co-operation of the UNHCR, other Governments, especially the Thai Government, and voluntary agencies in Australia.' When boats starting arriving regularly in Darwin Harbour, wharfies and others started to sound the alarm. Klaus Neumann in his dispassionate analysis of the period in his book Across the Sea: Australia's Response to Refugees — A History notes that MacKellar became half-hearted in his defence of the admission of boat people. On 22 November 1977, MacKellar addressed the NSW Branch of the Institute of International Affairs warning that 'no country can afford the impression that any group of people who arrive on its shores will be allowed to enter and remain…We have to combine humanity and compassion with prudent control of unauthorized entry, or be prepared to tear up the Migration Act and its basic policies'. He was backed up by Foreign Minister Andrew Peacock who said that Australia could not 'continue to indefinitely accept Asian refugees arriving unannounced by sea' and that 'Australia could not be regarded as a dumping ground'. A year later, there was an increasing flow of refugees out of Vietnam and into camps around South East Asia. The Fraser government insisted on the need for a co-operative international approach. When non-government agencies started to provide assistance to boat people on the high seas, MacKellar told parliament: 'I put the proposition that the people concerned with the project could not see a situation emerging where Australia would automatically allow the entry of any people that such a vessel happened to pick up.' On 29 June 1978, the Labor Party's spokesman on immigration matters, Dr Moss Cass, wrote a very inflammatory opinion piece in The Australian lamenting the arrival of over 1,000 boat people in Darwin Harbour, none of whom had been sent back to Vietnam. He said, 'The implications of a government policy which accepts queue jumping on this scale are obvious.' He was adamant that 'those refugees seeking residence in Australia who jump the queue by arriving on our shores without proper authorisation should not be given resident status, even temporarily'. It is important to appreciate that the notion that boat people are queue jumpers germinated at the very beginning of the first modest wave of boat people fleeing to Australia, and despite the heroic moral leadership of Malcolm Fraser. On 15 August 1978, the Labor frontbencher Clyde Cameron who had been Whitlam's Immigration Minister asked Fraser a rather hostile and insinuating question: 'Will he tell the Parliament what approaches were made by the United States of America which were in any way responsible for the decision to permit Vietnamese nationals to enter Australia without permits.' Fraser answered:

The United States of America has not attempted to influence procedures for entry to Australia. The Australian Government will at all times decide the requirements for entry to Australia. No Vietnamese nationals are permitted to enter Australia without entry permits. The 1634 boat refugees who have arrived in Darwin without prior authority were issued with temporary entry permits on arrival pending consideration of their applications to remain here.

The major political parties were agreed on the need to arrest the flow of boats, while being generous with the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees who then came through the camps in South East Asia under what later became the comprehensive plan of action in 1989. On 16 March 1982, Ian McPhee, Fraser's next immigration minister after MacKellar, provided Parliament with an update on the government's refugee policy restating, 'The decision to accept refugees must always remain with the Australian Government'. He told Parliament:

During my visit last year I reached the conclusion, commonly held by many involved in both the Indo-Chinese and Eastern European refugee situations, that a proportion of people now leaving their homelands were doing so to seek a better way of life rather than to escape from some form of persecution. In other words their motivation is the same as over one million others who apply annually to migrate to Australia. To accept them as refugees would in effect condone queue-jumping as migrants.

He called for a balance between compassion and realism. He announced progress with an orderly departure program aimed at arresting the flow of boats out of Vietnam. He reached agreement with his counterparts in Thailand and Malaysia how to arrest the flow and how to handle the numbers coming through. All this humanitarian effort was posited on the premise of stopping the boats coming uninvited to Australia.

There was a very moving scene at the state funeral of Malcolm Fraser when Vietnamese Australians thronged outside the church carrying placards which read: 'You are forever in our hearts: farewell to our true champion of humanity: Malcolm Fraser'. I honour Fraser, but not because he opened our borders to fleeing boat people coming in their tens of thousands. He didn't. He secured the borders, and then he led the nation in opening 'our arms and hearts to tens of thousands of refugees' as the novelist Tim Winton put it in his Palm Sunday address in Perth this year. Winton was wrong to claim that Fraser welcomed the boats. Winton was right to proclaim:

I was proud of my country, then, proud of the man who made it happen, Malcolm Fraser, whose greatness shames those who've followed him in the job. Those were the days when a leader drew the people up and asked the best of them and despite their misgivings, Australians rose to the challenge. And I want to honour his memory today.

Seeking the right balance between compassion and realism, between the human rights of asylum seekers and the national interest of a rich democratic country, we might find as much guidance from the memory of the last generation of refugees in their honouring of the last generation of political leaders who tried to forge a solution compassionate and fair to the many who were seeking asylum and acceptable to the voting public. I have concluded that stopping the boats is a precondition to finding a politically acceptable, compassionate and fair solution. It is time to quarantine the question of the morality of those stopping the boats, accepting the political imperative of stopping the boats if they can practically be stopped. The boats will be stopped. But they need to be stopped decently and fairly so that the community might then be encouraged and led to be more generous in opening the doors to a higher quota of refugees each year being selected by government from situations of acute despair, and in funding the international agencies and other governments caring for asylum seekers in transit. As one of the richest, most democratic countries in Southeast Asia, Australia will always be an attractive destination for some of the 59.5 million displaced persons in our world.

I have come to accept that my political leaders will always maintain a commitment to stopping the boats, no matter what political party they represent; but I insist that there is a need for international co-operation to determine how decently to stop the boats while providing an increased commitment to the orderly transfer of an increased number of refugees across our border so that they might live safe and fulfilling lives contributing to the life of the nation.

This cannot be done in Australia until we shut down the processing centres on Nauru and on Manus Island, until we accept that people should only be held in detention while issues of identity, security and health are determined, and while we negotiate arrangements with Indonesia, India and any other transit countries to which asylum seekers are being returned, replicating the new European regulation:

No person shall, in contravention of the principle of non-refoulement, be disembarked in, forced to enter, conducted to or otherwise handed over to the authorities of a country where, inter alia, there is a serious risk that he or she would be subjected to the death penalty, torture, persecution or other inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, or where his or her life or freedom would be threatened on account of his or her race, religion, nationality, sexual orientation, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, or from which there is a serious risk of an expulsion, removal or extradition to another country in contravention of the principle of non-refoulement.

It might then be possible for Australian officials to conduct prompt, reliable onboard assessments of asylum seekers on vessels determining whether it is appropriate to return them to their last port of call.

International law has its place in helping to change the policy settings of governments and to redirect the public debate. No doubt the Hirsi decision helped contribute to the development of thinking in Europe culminating in this recent regulation for dealing with boat people coming across the Mediterranean. It remains to be seen how effective Frontex Operation Triton is both at dissuading people from setting out on boats in the first place and then rescuing them when they do. With 280,000 people having entered the EU illegally in 2014, it is no surprise that the EU is now experimenting with its own externalized border, seeking to have Niger, Tunisia, Egypt, Morocco and Turkey prescreen intending migrants. The United Kingdom continues to be agnostic about the utility of proactive interception and rescue missions on the Mediterranean. When Operation Triton was being established, Baroness Anelay, the Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, told the House of Lords:

We do not support planned search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean. We believe that they create an unintended 'pull factor', encouraging more migrants to attempt the dangerous sea crossing and thereby leading to more tragic and unnecessary deaths. The Government believes the most effective way to prevent refugees and migrants attempting this dangerous crossing is to focus our attention on countries of origin and transit, as well as taking steps to fight the people smugglers who wilfully put lives at risk by packing migrants into unseaworthy boats.

The Spanish Parliament has now legislated to allow 'hot returns' of irregular migrants at the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in North Africa 'in order to prevent illegal immigration into Spain'. The borders of these enclaves are guarded by the Spanish border police and Moroccan forces. Stefan Kessler, the Europe senior policy officer for the Jesuit Refugee Service, says, 'There is the concrete danger that persons will be physically prevented from reaching the border crossing points and therefore will be blocked from lodging a protection claim'.

When considering the mission of international lawyers trying to humanise these externalised borders, I call to mind Martii Koskenniemi's prescient remarks:

International law increasingly appears as that which resists being reduced to a technique of governance. When international lawyers are interviewed on the Iraqi war, or on torture, or on trade and environment, on poverty and disease in Africa - as they increasingly are - they are not expected to engage in hair-splitting technical analyses. Instead, they are called upon to soothe anxious souls, to give voice to frustration and outrage. Moral pathos and religion frequently fail as vocabularies of engagement, providers of 'empty signifiers' for expressing commitment and solidarity. Foreign policy may connote party rule. This is why international law may often appear as the only available surface over which managerial governance may be challenged, the sole vocabulary with a horizon of transcendence - even if, or perhaps precisely because, that horizon is not easily translated into another institutional project. I often think of international law as a kind of secular faith.

None of us would want more realistic and more decent options in these most toxic of times to be forfeited by the simplistic invocation of international lawyers' opinions as if they were articles of faith. It is time to concede that none of us has a right to enter another country and that all of us have the obligation not to return anyone presenting at our border to a situation of persecution, torture, or cruel punishment. Though I doubt the possibility of the EU negotiating appropriate returns of asylum seekers to Libya in the foreseeable future, I continue to entertain the hope that Australia can negotiate appropriate returns to transit countries such as Indonesia for Iraqis, Afghans and Iranians and India for Tamils, so that Australia might then decently extend the hand of welcome to more of the world's 59.5 million displaced persons. For the moment, Australia is failing to strike the right balance between human rights and the national interest. It is stopping the boats indecently, violating the human dignity of those being held in unsatisfactory conditions in Papua New Guinea and on Nauru and failing to ensure appropriate safeguards are in place for the return of asylum seekers to Indonesia. For as long as international lawyers claim there is no possibility of a legally negotiated regional agreement for safe returns because they argue that asylum seekers have a right of entry to Australia to seek asylum, the Australian government, the Australian parliament, and the Australian courts will maintain, with impunity but with the occasional expression of outrage from international lawyers, a regime of returns insufficiently scrutinised for human rights compliance. I now accept that the boats will continue to be stopped (no matter which political party is in power), but that they should be stopped decently and in compliance with the legal regime enunciated by the European Union which has to deal with a far more pressing issue but subject to the more searching supervision of the European Court of Human Rights and of the European Parliament which has greater sensitivity to the human rights of asylum seekers than do their more pragmatic Australian colleagues.

I think it is time to take an ethical 'pass' on the stopping of boats. But we need to conduct closer ethical scrutiny on the downstream measures which initially were designed in part as deterrents. Once you've locked the door, there is no need or justification for maintaining a chamber of horrors inside the house to deter unwanted visitors! It's time to: close the facilities on Nauru and in Papua New Guinea; abandon the Cambodian shipment plan; negotiate a regional agreement for safe returns ensuring compliance with the non-refoulement obligation; and double the refugee and humanitarian component from 13,750 places to 27,000 places in the migration program, as recommended by the 2012 Expert Panel. The government should encourage further community participation in a refugee resettlement scheme which allows refugee communities and their supporters to increase the number of refugees resettled without taking the places of those refugees who would come anyway without community sponsorship. Why not increase the humanitarian program to at least the 20,000 places which were guaranteed prior to the 2013 election of the Abbott Government? And provide another 7,000 places for community sponsored refugees. I agree with novelist Tim Winton that there is a need for Australia to turn back, to 'raise us back up to our best selves'. That can best be done by securing our borders and increasing our commitment to orderly resettlement of more refugees, rather than by opening the borders, undermining the community's commitment to further assisting more of those 59.5 million people who are suffering displacement, most of them having no prospect of employing a people smuggler to get them to the border of a rich democratic country.

When revisiting his musing on the conflict between morality and politics, Gaita insisted that we should resist the temptation to see the conflict as one within morality. He insists that it is a conflict between morality and something else. He insists that political necessity stands outside the realm of morality:

When a politician, lucidly responsive to the imperatives of her vocation, says she must do what morally she must not do then, I believe, elaboration of what it means for her to do what she says she must do, or what it would be for her to fail to do it, reveals the distinctive kind of value with which that necessity is interdependent.

Gaita insists that it is 'a form of responsibility, different from moral responsibility'. I have the sense that Gaita is speaking of some form of existential collective imperative constitutive of the national identity. Like Luther who says, 'Here I stand. I can do no other', Kevin Rudd in 2013 and Richard Marles in 2015 ultimately came to declare, 'We must stop the boats', and in much the same way as Prime Ministers Fraser, Hawke and Howard did before them. Think only of Bob Hawke's response to the arrival of 220 Cambodian boat people in 1990:

Do not let any people, or any group of people in the world think that because Australia has that proud record, that all they've got to do is to break the rules, jump the queue, lob here and Bob's your uncle. Bob is not your uncle on this issue, other than in accordance with the appropriate rules. We will continue to be one of the most humanitarian countries in the world. But it is not an open-door policy.

These leaders reacted in this way not just so that their party could have a real chance of being elected, not just so that they might improve the processing of asylum claims onshore while securing our borders, but so that they could lead the people and be led by the people with a commitment to that distinctively political necessity of Australian public life best summed up by John Howard in his 2001 election speech: 'we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come', and with a commitment to that universal political imperative that the world be made a safer place for at least a handful of the globe's 60 million displaced persons. That's the politics of evil and a very untrendy truth. I never thought I would hear myself utter it, and I am happy to be corrected.

We should forthwith close the detention facilities on Nauru and on Manus Island. These are evil places. All those detained should be brought to the Australian mainland. We should detain asylum seekers on the mainland only for the purposes of health, security and identity checks. Once these checks are complete, asylum seekers ought be allowed to live in the community with work rights and basic social security. We should abandon the Cambodia solution. We should increase our annual quota of humanitarian places. We should commit to diplomatic efforts aimed at enhancing the multilateral undertakings to protect asylum seekers in South East Asia and to provide permanent solutions for refugees. But the quid pro quo is prompt screening of boat people on the high seas, or even on arrival at Christmas Island, to assess whether they are in direct flight from persecution IN Indonesia. If not, they can be returned safely and with dignity to Indonesia. Asylum seekers in Indonesia should then be processed in a real queue and protected by Indonesia, UNHCR and IOM — with assistance from Australia, conceding that there will be limits to which the Indonesians will agree to enhanced protection and processing because they will not want to set up a magnet effect.

If we could agree that the political imperative of stopping the boats requires suspension of moral judgment of those enacting the policy, we might then engage in the moral and political assessment of post-arrival policies which do not pass muster and which no longer serve any useful purpose. There is one advantage of stopping the boats upstream. No longer is there a need for downstream deterrents. Those deterrents now lack all moral coherence. The dirty hands of their architects and advocates need to be exposed for the good of those suffering ongoing abuse in our name in Nauru, on Manus Island, and in our community without adequate access to work or welfare. The front door is now locked, so its time to close down the chamber of horrors. If the architects remain convinced that the boats can continue to be stopped upstream only by maintaining the downstream bundle of evils, then they need to show remorse and we the voters should be less forgiving for the ongoing evil committed in our name. It is one thing to posit national identity and politics on the securing of borders by turning away all comers except those with visas or those in direct flight from persecution; it is another to posit national identity and politics both on the continuing abuse and punishment of asylum seekers within the purview of the polity so as to send a message to other would-be arrivals, and on the continuing corruption of more fragile polities like Nauru and PNG. Stopping the boats has been part of our national narrative, and probably part of our national identity, since the first boat people arriving in Darwin Harbour in the 1970s were called queue jumpers. Punishing and excluding those who make it has no place in our national narrative. For the good of the Commonwealth, and our mendicant Pacific neighbours, such punishment and exclusion should cease.