'You can't go around building a better world for people. Only people can build a better world. Otherwise it's just a cage.'

When I heard English author Terry Pratchett had died, I immediately jumped online to start looking through some of my favourite quotes from his books. The above, from Witches Abroad, is one of many that have accompanied me over the years.

When I heard English author Terry Pratchett had died, I immediately jumped online to start looking through some of my favourite quotes from his books. The above, from Witches Abroad, is one of many that have accompanied me over the years.

His 44 Discworld novels could be broadly described as comic fantasy, or fantasy satire, and yet that's really just the starting point for the immense variety of complicated ideas they explored in such a fun, joyous way.

Perhaps strangely for someone whose work is so grounded in atheism, Pratchett has had a profound impact on my religious faith.

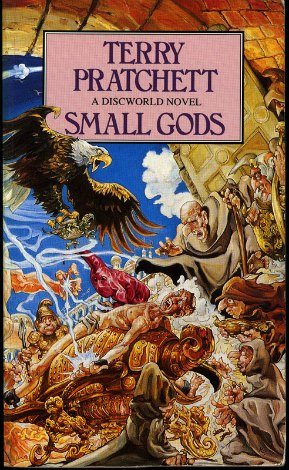

Pratchett had a lot to say about religion. In 1992 book Small Gods, he joked that 'gods like to see an atheist around ... gives them something to aim at'. He also had more cutting things to say about religious faith, including this observation during one scene: 'They were engaged in religion. You could tell by the knives (it's not murder if you do it for a god).'

What set Pratchett apart from many other critics of religion of these times was his recognition of the basic human need for meaning, and the beautiful way so many of his books tried to find a positive, life-giving way to exist in a universe where gods either don't exist, or aren't worth believing in.

Take this example, from his 1997 Christmas-themed satire, Hogfather, involving one of his most iconic characters, Death:

'All right', said Susan. 'I'm not stupid. You're saying humans need... fantasies to make life bearable.'

NO. HUMANS NEED FANTASY TO BE HUMAN. TO BE THE PLACE WHERE THE FALLING ANGEL MEETS THE RISING APE.

'Tooth fairies? Hogfathers?'

YES. AS PRACTICE. YOU HAVE TO START OUT LEARNING TO BELIEVE THE LITTLE LIES.

'So we can believe the big ones?'

YES. JUSTICE. MERCY. DUTY. THAT SORT OF THING.

'They're not the same at all!'

YOU THINK SO? THEN TAKE THE UNIVERSE AND GRIND IT DOWN TO THE FINEST POWDER AND SIEVE IT THROUGH THE FINEST SIEVE AND THEN SHOW ME ONE ATOM OF JUSTICE, ONE MOLECULE OF MERCY. AND YET. AND YET YOU ACT AS IF THERE IS SOME IDEAL ORDER IN THE WORLD, AS IF THERE IS SOME ... SOME RIGHTNESS IN THE UNIVERSE BY WHICH IT MAY BE JUDGED.

'Yes, but people have got to believe that, or what's the point...'

MY POINT, EXACTLY.

Christians (and I'm one of them) often fall into the trap of portraying atheism as a desert — a place where all values are stripped away and anything goes. Atheists don't see it that way, of course.

But one of the things I often challenge atheists about is whether they can move beyond talking about all the things wrong with religion, and start putting forward an alternative way to live — to build another place to live rather than the desert.

Pratchett did that in his works. His genius was turning the desert into the Discworld — a planet that sat on the back of four elephants, perched on a gigantic tortoise that made its way through the universe. He created a place that was full of gods and enchantment, then populated it with heroes grounded in objective scientific materialism.

One of Pratchett's more recent characters is Tiffany Aching, a young witch who is the main protagonist in four young adult novels — The Wee Free Men, A Hat Full of Sky, Wintersmith, and I Shall Wear Midnight. Unlike other YA protagonists like Harry Potter, what sets Aching apart, what gives her the power that she wields, is not something mystical or metaphysical — it's her mind.

Aching's 'First Sight' helps her see 'what is really there', rather than 'Second Sight' which 'shows people what they think ought to be there'. The book also goes into 'second thoughts' (thoughts you think about the way you think), and 'third thoughts' (thoughts you think about the way you think about the way you think) and so on to fourth thoughts (which tend to cause Tiffany to walk into door frames).

It can be challenging reading Pratchett as a religious believer, but it can also be incredibly valuable. Like many atheists who critique religion, he is usually spot on when he points out the hypocrisies that believers are capable of, and the dangers of fanaticism in all its forms.

But conversations like the one above between Death and Susan show that there can be no great gulf between someone who believes in a purely material universe and someone who believes that there exists something beyond that universe, so long as they can agree that justice, mercy and duty are important values to uphold.

More than that, characters like Aching can actually challenge Christians to improve the way that they live their lives as believers. Are we using our first sight when we look at the world around us, or are we using our second sight — seeing things as we think they ought to be rather than the way they are?

And even more importantly: How can we train our 'First Sight' on God, to see what God really is, rather than what we think God ought to be?

I'll be forever grateful to Terry Pratchett for teaching me something that atheists who love and enjoy writers like Tolkien or C. S. Lewis have perhaps known all along — that you don't have to completely agree with someone to be inspired and informed by their words.

Michael McVeigh is the editor of Australian Catholics magazine.