On the centenary of ANZAC Day, I had the honour of preaching in the Harvard Memorial Chapel. The church full of Australians and New Zealanders included a handful of Americans and Turks. We were very privileged to have the Turkish Consul General participate in the ceremony. His involvement transformed the event. I commenced my remarks with the observation: ‘It is fitting that we, Australians, New Zealanders, Turks and Americans should gather in this place to mark the centenary of Anzac Day, the day on which Australians and New Zealanders landed in the stillness of the early dawn on the Turkish shoreline wanting to assist with the Allies’ advance on Constantinople, now Istanbul, the day on which the Turks commenced a successful, eight month campaign to defend their homeland against the assault.’

Regardless of what post facto moral case might be made against the Australians and New Zealanders invading that part of Turkey at that time (and I am not one who argues that a convincing moral case against the invasion is to be made), no one could seriously suggest that the Turks were not morally entitled to defend their homeland against assault.

In my homily at Harvard, I went on to say:

We remember the 130,000 who were killed on that blood-soaked peninsula during the Gallipoli campaign, and the other quarter of a million who were wounded. A century on, we have gathered more inclusively and not just to pray for the 44,000 Allies who died, but also for the 86,000 Turks who perished in their trenches opposite them. Being ANZAC Day, we particularly call to mind the 8709 Australians and 2779 Kiwis who died.

We recall the innocence of the soldiers – many aged the same as many of those who today study here at Harvard – and the human values that they embodied of courage and mateship. We recall too the reality, routine and relentlessness of their fighting, their sufferings, and their deaths. We also recall the idealism, the hope, and perhaps even the naivety of empire which motivated and sustained them and those who sent them to battle.

Having just spent the past academic year as a visiting professor in the law school at Boston College, I had the pleasure of encountering three writers on different aspects of the morality of war: the Oxford theologian Nigel Biggar who has recently published In Defence of War (Oxford University Press, 2013), Fr Ken Himes OFM from Boston College who is about to publish Drones and the Ethics of Targeted Killing and MaryEllen O’Connell, professor of international law from Notre Dame who is the author of What is War? An Investigation in the Wake of 9/11 (Martinus Nijhof/Brill, 2012). In January 2015, Biggar and O’Connell went head to head at the opening plenary of the Society of Christian Ethics Conference in Chicago.

I have been particularly stimulated by Biggar’s writings on war and peace because he thinks that many of us Christians (and I am probably one of those in his sights) are too pacifist in our approach to moral questions about war. I have long been challenged by George Orwell’s famous remark: ‘Those who “abjure” violence can do so only because others are committing violence on their behalf.’ We who live behind secure borders on an island nation continent where we elect governments committed to stopping the boats by hook or by crook have to accept that the peace, prosperity and security we enjoy is bought at a price paid by others who are cheated peace, prosperity and security.

I am challenged by Biggar’s description of the dilemma which confronts each of us in a world marred by violence and injustice. Biggar says:

This is the dilemma: on the one hand going to war causes terrible evils, but on the other hand not going to war permits them. Whichever horn one chooses to sit on, the sitting should not be comfortable. Allowing evils to happen is not necessarily innocent, any more than causing them is necessarily culpable. Omission and commission are equally obliged to give an account of themselves. Both stand in need of moral justification.

Given the ready access we have to international media and the world wide web, we can no longer plead ignorance of the trouble going on in our world. Those of us who are purist pacifists can presumably put a coherent case for eschewing violence in all cases, even were a madman to be imminently threatening the lives of our most vulnerable loved ones. Others of us could still claim to be Christian while making a case for self defence, even the killing of the rampaging murderer in the children’s play ground.

Those of us who concede the case for war insist on the need for legitimate authority to commit to war only in circumstances complying with the conditions for a ‘just war’. Secularists as well as religious persons claim a capacity to list those preconditions. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states at #2309:

The strict conditions for legitimate defense by military force require rigorous consideration. The gravity of such a decision makes it subject to rigorous conditions of moral legitimacy. At one and the same time:

- the damage inflicted by the aggressor on the nation or community of nations must be lasting, grave, and certain;

- all other means of putting an end to it must have been shown to be impractical or ineffective;

- there must be serious prospects of success;

- the use of arms must not produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated. The power of modern means of destruction weighs very heavily in evaluating this condition.

These are the traditional elements enumerated in what is called the “just war” doctrine.

The evaluation of these conditions for moral legitimacy belongs to the prudential judgment of those who have responsibility for the common good.

Though we Christians concede the need to render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, we do insist that we retain the right and duty to scrutinize Caesar’s actions for compliance with the moral imperatives we deduce from the teachings of Jesus and for our church traditions. In politics, it is more often a matter of timing and seizing the moment than of determining how to apply the moral principles to the issue at hand. Those of us who consider ourselves ambassadors for peace need to be ever alert. You will remember that when committing Australia to the 2003 Iraq War, Prime Minister John Howard was asked about the chorus of church leaders who had expressed opposition to the planned armed intervention. John Howard told the National Press Club:

There is a variety of views being expressed. I think in sheer number of published views, there would have been more critical than supportive. I thought the articles that came from Archbishop Pell and Archbishop Jensen were both very thoughtful and balanced. I also read a very thoughtful piece from Bishop Tom Frame, who is the Anglican Bishop of the Australian Defence Forces. The greater volume of published views would have been critical, but I think there have been some very thoughtful other views and the ones I have mentioned, I certainly include in them.

Being an accomplished politician, Howard managed to create the perception of the moment that the two Sydney archbishops were more closely aligned to his position than were most other church leaders. It was quite misleading for him to group Jensen and Pell with Tom Frame who later admitted that he had lost his ‘ecclesiastical virginity’ when temporarily convinced of the morality of the war by Howard and his military advisers.

Archbishop Peter Jensen was quite prompt in correcting the misperception created by Howard. Within a week of the Prime Minister’s appearance at the National Press Club, Jensen said, ‘For my own part I remain unpersuaded that we ought to have committed our military forces, but I recognise the limitations of my judgment and the sincerity of those who differ.’ Archbishop Pell, known to be a close friend of John Howard, left the misperception hanging in the air for fourteen months before he told a radio audience in Ballarat:

I never publicly endorsed the second war in Iraq. I wrote publicly about it and I said at that stage the case was not established. They said they were going to Iraq basically on two grounds: that there were weapons of mass destruction there; and that Saddam was actively supporting Al Qaeda. Neither of those two grounds has been established. ... I didn't endorse the war.

In hindsight, and wanting to learn lessons for the future in the wake of a conflict which so demonstrably failed to fulfil the conditions for a just war, we can say that it would be better for our church leaders to be more immediately and publicly assertive in questioning the legitimacy of a proposed armed intervention, regardless of the immediate effect on the morale of the troops.

I would like to touch on two modern developments in warfare – one legal, and one technological. The legal development relates to the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ framework (RTP) which has been developed by international NGOs and given qualified endorsement by the UN. In the wake of ghastly events like the Rwanda genocide, the international community was seeking better criteria which could authorise armed intervention in a nation state even without that state’s approval, and perhaps even without the need for a resolution from the UN Security Council given that the five permanent members of the Security Council retain a veto over any proposed resolution. Everyone concedes that the nation state carries the primary responsibility for protecting its own population from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing, and their incitement. No doubt, the international community has a responsibility to encourage and assist nation states in fulfilling this responsibility towards all persons within their jurisdiction. The international community has a responsibility to use appropriate diplomatic, humanitarian and other means to protect populations from these crimes. What is to be done if a state is manifestly failing to protect its own population? The international community must be prepared to take collective action to protect populations, but presumably in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.

According to existing international norms a state may utilise armed force within another state’s borders in three circumstances:

- if the ‘invaded’ state consents to the ‘invading’ state’s action.

- when the U.N. Security Council authorises the intervention.

- when armed force is used in accord with ‘invading’ state’s right of self-defence against attack.

But what if the UN Security Council withholds authorization simply because one of the permanent members (P5) exercises the veto in their own national self-interest, in order to further their own geo-political objectives regardless of the humanitarian need of the moment? What then would constitute the appropriate authority for armed intervention. We might consider the NATO intervention in Kosovo which was done without UNSC approval. Legitimate authority and UNSC. Some international NGOs are now pushing ‘The Responsibility Not to Veto’. They argue that the permanent five members of the UN Security Council (P5) should agree not to use their veto power to block action in response to genocide and mass atrocities which would otherwise pass by a majority. At the time of the Iraq War, I conceded that it might be impossible to gain UNSC authorization even if the criteria for a just war could otherwise be satisfied. But thinking the criteria could not be satisfied, I postulated that we would be entitled to use the democratic western states of the UNSC as an appropriate sieve for judging the likelihood that the criteria would be fulfilled. On this approach, we should not have proceeded to join the US in alliance in Iraq unless we could first win the support of the Germans and the French. This ‘sieve’ could be used to assess the case for intervention in circumstances (2) and (3).

The technological development relates to the US deployment of drones by the Pentagon in warzones and, more worrying, by the CIA outside warzones, in places like Pakistan and Yemen. Drones are also known as ‘Unmanned or Unoccupied Aerial Vehicles’ (UAVs) or ‘Remotely Piloted Aircraft’ (RPAs). The US military now annually trains more pilots for these vehicles than for traditional military jet fighters. The pilots come to work in downtown offices wearing their jeans and T shirts drinking the Starbucks and eating their MacBurgers, going home to the wife and kids after each shift when they have spent the day tracking HVTs (high value targets) and ‘taking them out’. The Americans insist that these are not extra-judicial killings for past wrongs but pre-emptive justified strikes against individuals who are an imminent threat to the USA. The US Administration insists that they abide by a self-imposed code of behaviour when using drones:

1.) there must be a legal basis for using lethal force;

2.) the target . . . poses a continuing imminent threat to U.S. persons. It is simply not the case that all terrorists pose such a threat;

3.) the following criteria must be met:

a. near certainty that the terrorist target is present;

b. near certainty that non-combatants will not be injured or killed;

c. an assessment that capture is not feasible at the time of the operation;

d. an assessment that the relevant governmental authorities in the country where action is contemplated cannot or will not address the threat to U.S. persons;

e. an assessment that no other reasonable alternatives exist to effectively address the threat to U.S. persons.

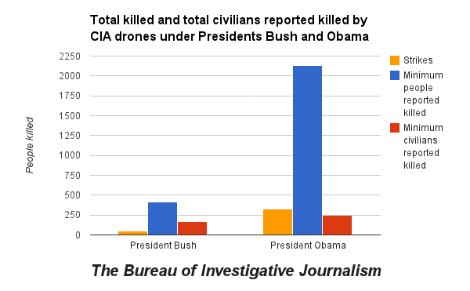

Many Australians would be horrified to learn that the drones program depends on Australian co-operation with facilities such as Pine Gap providing necessary communications in tracking and taking out targets. They would be even more aghast to learn that the Obama Administration has escalated the use of drones way beyond the level used by the previous Bush Administration.

It is only a matter of time before other state and non-state actors get access to drones. They cannot be used in countries like Australia which have secure air defence. But there will be nothing to stop unscrupulous actors using them in developing countries without secure air defence. Is it not time to develop an international code of practice for drone use with an international monitoring regime? This is one development which should not be left simply to American exceptionalism with the political assurance from the US Administration that they can be trusted to use drones only in the most morally compelling of circumstances.

Before the recent UK election, there was significant agitation in Scotland during the campaign about the UK’s Trident nuclear program. Scottish nationalists like Alex Salmond were quite outspoken. The Oxford theologian Nigel Biggar bought into the fray with this compelling observation:

What remains, then, but despair and inertia? Hope remains – but only of a certain kind. It needn’t be impatient and reckless. It needn’t only take the form of relentless, fingers-in-the-ears Project Optimism, whether Donald Rumsfeld’s or Alex Salmond’s. It can be patient and sober instead. This kind of hope remains that, as in the past so in the future, the careful management of nuclear deterrence will continue to discourage tyrants from chancing their aggressive arm; that the incremental strengthening of international norms and institutions will bolster trust and relax tension; that more non-nuclear states can be dissuaded or stopped from acquiring nuclear weapons altogether; and that the stockpiles of those already armed can be further reduced. So we can hope, soberly and prudently. And those of us who’re religious, knowing what can befall the best laid plans of mice and men, will also pray to God almighty to meet our efforts with the miracle of good fortune. So there’s room for hope in our prudence.

In that spirit, I would like to conclude with the ANZAC Prayer which I prayed in the Harvard Chapel on the ANZAC Centenary Day (which was a variant on the prayer used at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra):

Lord Our God, on this day, 100 years ago, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, at Gallipoli, made immortal the name of Anzac and established an imperishable tradition of selfless service, of devotion to duty, and of fighting for all that is best in human relationships.

O Lord, we who are gathered here today from both sides of that conflict remember with gratitude the men and women who have given, and are still giving all that is theirs to give, in order that the world may be a nobler place in which to live.

And with them, Lord, we remember those left behind to bear the sorrow of their loss.

We dedicate ourselves to taking up the burdens of the fallen and, with the same high courage and steadfastness with which they went into battle, to setting our hands to the tasks they left unfinished. Lord, we dedicate ourselves to the service of the ideals for which they died. With your help, O God, might we give our utmost to make the world what they would have wished it to be, a better and happier place for all of its people, through whatever means are open to us.

We make this prayer through Christ Our Lord. Amen.

I commend all of you who dedicate your energies and your thoughts to these vexed issues of war and peace. Whether we be purist pacifists or just war advocates, we need to be able to give an account of our stand both to those suffering at the hands of ruthless oppressors and to those put in harm’s way by armed interventions conducted in our name.

This is the text of an address delivered at St Joseph’s Church, Newtown, Sydney, on 14 June 2015.