‘Giving a voice to the cognitive dissonance required to being a woman under the patriarchy robbed it of its power.’

As we drove home from the Barbie movie, I asked the granddaughters what they understood about the phrase ‘cognitive dissonance’. They knew that I was going to bother them with questions, but they are tolerant. At 12 and 9, they haven’t yet fully realised how ignorant and out of touch I am, (that will come when they are around 14 though they are already critical of my parking, my tech skills and my cooking). But they were quite happy to come along and watch a film even if they knew there would be a price to pay afterwards when I asked questions. Primed with violently coloured slushies and a giant vat of popcorn, they trooped in and I think were as surprised as I was when I liked it.

But the questions were essential, because they were the perfect age-group for the movie. Or were they? The film asks some pretty deep questions itself. And they of course, have had the kind of upbringing where their old grandma would snark at people who tried to give them Barbies when they were younger, because now being over five, they are too old for these dolls yet not too old for films about them.

To do them justice, they had a fair go at ‘cognitive dissonance’, because they had picked up a good bit of the meaning from context (one of the numerous good things about the film).

‘Well, it happened when the Barbies realised the truth,’ said the older one.

I pursued it happily: ‘You know when music doesn’t work, when notes don’t go together?’

They made hmm noises. Gradually I tried to give them the etymology:

‘ “Cognitive” means “about knowing”,’ I said. ‘ “Dissonance” is when something doesn’t go together with what it’s supposed to go with.’

They tolerated me during all this. Love goes a long way to building tolerance.

What really helped their understanding was director Greta Gerwig’s management of epiphanies in the film: we expect such dawnings in the main characters, but not all realisations are welcome. Poor old Ken is left pretty much adrift morally and temporally, his raison d’être removed whenever Barbie rejects him, which she does, frequently and especially at the start of the movie when she is in her pink Utopia, in the world where women are perfect role models in every career possible. President, Nobel winner, doctor, vet, heroine-in-a-wheelchair: every task for which you can imagine a costume or accessory is there.

Ken: You guys aren't doing patriarchy very well.

Corporate Man: We're actually doing patriarchy very well

[lowers voice]

Corporate Man: ... we're just better at hiding it.

Greta Gerwig has placed – sharply – the measure of little girls’ dreams against the reality of the world they must navigate as they get older. The film begins with a cheeky parody of the beginning of 2001: Space Odyssey. Instead of apes playing with bones we have little girls playing with baby dolls, and instead of the mysterious monolith there is the entirely familiar first Barbie, pony-tailed, busty, wasp-waisted and high-heeled. Whereupon the little girls, somewhat disturbingly, smash their baby dolls and embrace the new play-dream.

No more simulacra of motherhood – now we have the simulacra of careers, of an ideally formed and clothed young woman in a perfect career in a perfect house. Add her perfect friends, pets, cars and boyfriend and you have liberation turned into burdensome expectations. For you must be popular, beautiful and perfect. And clever, and successful.

‘I’m just so tired of watching myself and every single other woman tie herself into knots so that people will like us. And if all of that is also true for a doll just representing women, then I don’t even know.’

I remember my little sister being given a Barbie doll for her birthday in the early ‘60s. We all took off its clothes and inspected the unbelievable boobs. How could they dare to give the doll a recognisable female form? Not really of course: more like a shop mannequin. The feet were strange, constantly on tiptoes, but we understood that this was bold and liberating and new as well because this doll was going to wear high-heeled shoes like a ‘real’ woman would – not the usual flat feet that could only fit Mary Janes.

This of course was before the mid-to-late ‘60s when Twiggy became the face – and body – of what girls and women wanted to be. A girl whose face looked like a doll’s and a body that did not disrupt the straight lines of the Mary Quant mini-dresses that erased all curves. Boobs were suddenly untidy, inelegant. But Barbie’s boobs somehow didn’t ever make her look pregnant in a shift dress. Perhaps the other bodily proportions helped: the elongated legs, the tiny waist and hips, the huge head.

Suddenly the pointy cones of brassieres became flatter, but not less prescriptive in shape. We adjusted our attitudes and our eyes to see beauty in a different way. Barbie’s shape didn’t change but her dresses were now shorter, more Paco Rabanne than Christian Dior New Look. Our shoes in the ‘60s changed, though. High heels and pointy toes were for old ladies, and no-one wanted to be that. Barbie still managed to survive the era of Twiggy and Shrimpton and was more at home with subsequent eras when shoes got spikier and dresses got foofier.

And the demands on women in careers didn’t change: look great or be considered unprofessional. Clothes designers got a lot crazier and less in touch with women’s shape over the years as models’ proportions lengthened and yet still had to suggest voluptuousness. At least any normally lean woman could enjoy the fact that Twiggy had liberated her from needing to have a big bust. But the eighties and subsequent decades changed that. Plastic surgery sucked fat away from normal thin women and sewed plastic balloons on their chests. Being thin enough wasn’t enough.

It became harder for ordinary-looking women to find flattering clothes that fit, but Barbie certainly added no solutions. The Barbie movie addresses a great deal of this and does it deftly and pointedly.

‘It is literally impossible to be a woman. You are so beautiful, and so smart, and it kills me that you don’t think you’re good enough.’

Thank God, my girls wear whatever they like, and often this will be dresses for parties, and pants and shorts or whatever is comfy for everyday stuff, and Oodies whenever they’re feeling even slightly nesh. (I have a Gryffindor Oodie, a not-entirely-unironic Chrissie present from a loved one. When the girls visit, I don’t get to wear it because it reminds them of their own Oodies at home.)

The day before we went to the movie, all the kids in their school were invited to come to school dressed as scientists for the end of Science Week. My nine-year-old planned ahead, ganked one of her dad’s white work shirts as a lab coat, donned safety glasses and announced that she was a researcher in a lab examining ‘a virus’. A quickly donned mask from the glove box in the car as she was dropped off that morning completed the look. The twelve-year-old had a problem: no more faux-lab coats were available because she’s too tall to make it look like anything other than a borrowed shirt. A conversation with her teacher elicited the exciting fact that geologists would probably wear cargo pants in the field. ‘And I’ve got cargo pants!’ she exulted and went off to school in said pants and a hoodie (not Oodie); a proper little geologist.

Barbie would applaud: in her world, clothes maketh the girl as much as white shirts and cargo pants made my girls scientists that day at school. Donning scientist’s clothes made them enter that world in their imaginations. Very Barbie. But perhaps a seed might be sown in their real-world ambitions.

In the end, the girls quite liked the film: not as much as the Harry Potters or Lord of the Rings ones, but it was OK. I asked them if they thought anything was missing.

‘Yes’, said my older girl. ‘Dads. There were no dads at all in the film.’

She was right. The storyline does have surprises and insights. But it hasn’t got room for everything: after all Greta Gerwig is only a woman. Does she have to do every damn thing just to please everyone?

‘Like, we have to always be extraordinary, but somehow we’re always doing it wrong …'

Juliette Hughes is a freelance writer.

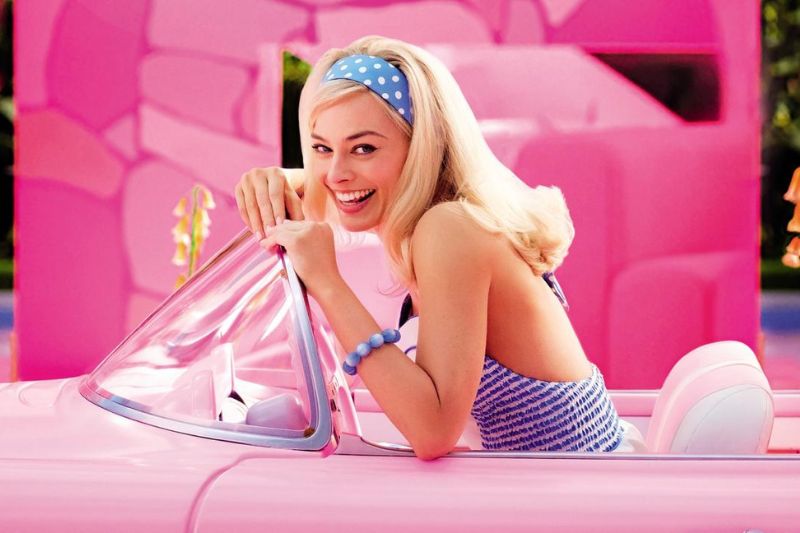

Main image: Margot Robbie. (Warner Bros)