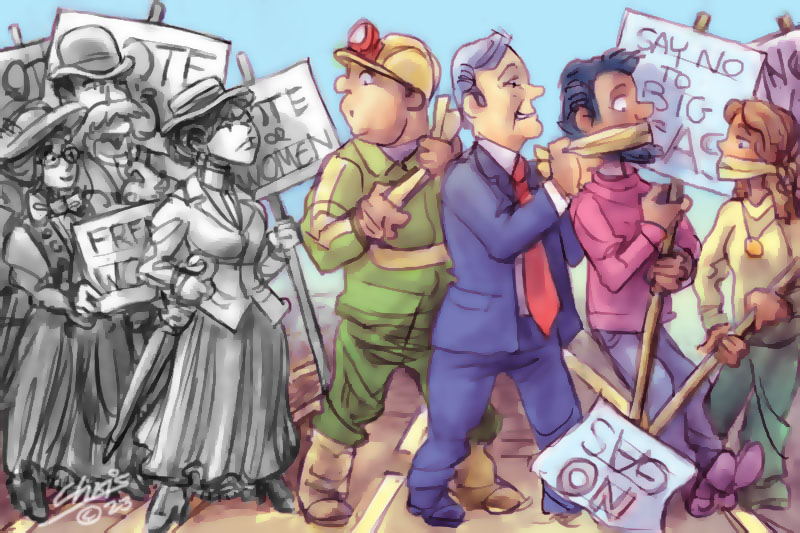

In 1894, after many years of difficult campaigning by both women and men here in South Australia, their suffragette leader Mary Lee was amongst them in Parliament when the Bill was passed giving women the right to vote. South Australia thus became the second place in the world to give women the vote and the first Parliament in the world where women could themselves become a Member of Parliament. What a proud history. At the Third Reading debate, the Advertiser reported that, ‘Ladies poured into the cushioned benches to the Left of the Speaker and relentlessly usurped the seats of the gentlemen … They filled the aisles and overflowed into the gallery to the right’. Lucky them! If they were doing this 129 years later, in May 2023, they would have each been fined up to $50,000 or imprisoned for three months. Such is the extraordinary law just passed by the women and men in our South Australian House of Assembly. What a blight on our proud SA democratic history.

On 18 May, anti-protest laws were rushed through the State’s lower house following a rally the previous day by climate action group Extinction Rebellion outside the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association conference in Adelaide. This was the gathering where the State Minister for Energy and Mining, Tom Koutsantonis, made the incendiary declaration to Santos and the other assembled companies: ‘the South Australia government is at your disposal’.

The changes introduced by the Summary Offences Act (Obstruction of Public Places) Amendment Bill increase the maximum fines for disruptive protests from $750 to $50,000 along with potential jail time.

Sadly, SA is not an outlier here, but is rather in step with the rest of the country with similar ‘draconian’ laws passed just last year in VIC and NSW regulating protests, albeit with smaller maximum fines.

Nevertheless, it was galling to discover that this extraordinary move merited just 22 minutes of ‘debate’ in the SA House of Assembly. It was even more vexatious to find the idea was first broached on talk-back radio by the opposition leader, David Speirs.

One can imagine the consternation within the House as protestors from Extinction Rebellion abseiled over a bridge in the Adelaide CBD, causing major disruption to traffic. Spiers declared that the new legislation ‘just passed parliament in almost record time … in a bipartisan way. It’s about increasing the fines for people who take part in reckless protest. And that’s what we saw undertaken by Extinction Rebellion in Adelaide’s Central Business District yesterday. Roads closed, ambulances not being able to get to and from the Royal Adelaide Hospital, people having to cancel day surgery they’d waited weeks for.’

While it is certainly true that many people were inconvenienced by the 90-minute traffic holdup as police cordoned off the entire road, the Ambulance Union has strongly opposed suggestions that ambulances were hindered. Indeed, at a rally on 30 May, the secretary of the Ambulance Employees Association, Leah Watkins, was a key opponent of the Bill to be put forward that day to SA’s Upper House: ‘This Bill fundamentally threatens our ability to take action like this, in the interests of our members and the South Australian community.’ Similar concerns were expressed by SA Unions President Dale Beasley.

'The swift passage of these anti-protest laws in SA signals a significant shift in the political climate. In stark contrast to historical precedents and national practice, these laws were passed without comprehensive public debate or consultation, raising serious concerns about civil liberties and democracy.'

No opportunity was afforded by the government for official community debate. But in the days leading up to the Bill’s appearance before the Legislative Council, there were two well-attended rallies, and over 80 civil organisations had registered to be part of the full-page advertisement opposing the Amendment — including Amnesty International as well as many environmental groups like the Conservation Council of SA — which appeared in The Advertiser on 26 May. On 30 May a double-page advertisement featured, funded by seven groups including the South Australian Council of Social Service and SA Unions, urging defeat of the Bill ‘to protect our fundamental rights and freedoms’. Staffers of Legislative Council members reported a ‘great number’ of emails and phone calls flooding their offices.

Both major Law Associations within SA strongly advised government against the passing of the proposed Amendment to the existing Summary Offences Bill. The government held firm to its claim that nothing had changed for peaceful protestors.

The Legislative Council debate on the Amendment began at 4.15pm on 30 May. Rob Simms, SA Greens, and Frank Pangallo, SA Best, did all in their power to extend the debate, each speaking at great length. Of the four proposed amendments, three were rejected with only one amendment supported by the overwhelming Labor/Liberal majority. This at least lessened the likelihood of homeless people being charged under the crushing new punishments for obstructing public places, simply by sleeping rough. With pleas for adjournment denied, the new Amendment was passed just before 7am.

Australian Lawyers for Human Rights (ALHR) president Kerry Weste noted that the amendment had the potential to impact a wide range of protest activity — students, healthcare workers, First Nations people and their allies, environmental campaigners, and disabled campaigners, saying that ‘when we violate the right to peaceful protest, we undermine our democracy’. She emphasised that any South Australian resident who ‘directly or indirectly obstructs a public place in order to campaign for their rights faces a life-changing prison sentence and crippling fines.’ Reminding us of what is at stake, she observed that ‘without the right to assemble en masse, disturb and disrupt, to speak up against injustice we would not have the eight-hour working day, and women would not be able to vote.’

On reflection, it is hard not to see that the power of the ordinary person in South Australia was diminished in those two weeks in May when the whole state was seemingly served up to potential exploitation by resources companies with that declaration from the Minister for Energy and Mining: ‘the South Australia government is at your disposal’. What of the Aboriginal Heritage Act, the Environment Act and any other of the Acts which seek to protect resources of land and waters for the good of current and future generations of South Australians? And when a previous government’s agenda, no matter how punitive for its citizens, was adopted with such speed through the House of Assembly and then confirmed in the Legislative Council.

Such a contrast with the SA Labor government’s historical reaction to protest in public places. One instance: In NA[I]DOC Week, 1972, a brave group of Aboriginal protestors, led by their ‘Ambassador’ Colin McDonald, set up camp as the Adelaide Aboriginal Embassy in the North Adelaide parklands, proclaiming, ‘Well, we’re just taking back a piece of our land’. Ambassador McDonald summed up the Embassy’s purpose: ‘Just like the Embassies in Perth and Canberra, we want to make people aware that we, the native australians [sic], don’t own any land in Australia. Horses, cattle and sheep have more land rights than us.’ A note the Lord Mayor of Adelaide sent to the Town Clerk read: ‘Somebody has just rung me and said they heard a broadcast from Sydney that the Premier Mr Dunstan [interstate on government business] had said he would take action immediately if the Adelaide City Council took any steps to remove aboriginals [sic].’ (ACC Archives)

The current response by the government of South Australia also stands in contrast to instances on the national front: for example, in 1997, after long public debate, the parliamentary findings of the Right to Protest were published regarding protests in the national capital. The booklet, sent to me as a contributor, summarised the time, number and names of those making written submissions both in the 37th (114 submissions) and 38th (35 submission) federal parliaments. As well, there was a Public Hearing, with 70 witnesses from organisations and 17 individuals.

The swift passage of these anti-protest laws in SA signals a significant shift in the political climate. In stark contrast to historical precedents and national practice, these laws were passed without comprehensive public debate or consultation, raising serious concerns about civil liberties and democracy. We must remember our right to protest is a fundamental tool for ensuring government accountability and for advocating justice, equity, and respect for all.

So much for the evolution of our democratic rights with time.

Michele Madigan is a Sister of St Joseph who has spent over 40 years working with Aboriginal people in remote areas of SA, in Adelaide and in country SA. Her work has included advocacy and support for senior Aboriginal women of Coober Pedy in their successful 1998-2004 campaign against the proposed national radioactive dump.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.