How to Draw the Line on Oil and Gas Reserves:

Finding a Just Settlement between Australia and Timor-Leste

Fr Frank Brennan SJ AO

UCD Law School, Dublin

24 September 2014

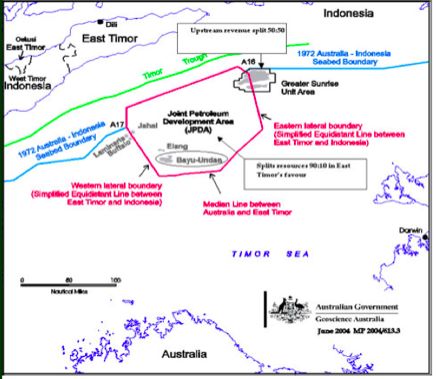

In 2006, Australia and Timor-Leste signed the Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS). The treaty came into force early in 2007 with a provision requiring the submission and approval of an appropriate development plan for the Greater Sunrise oil and gas deposit in contested waters within six years (February 2013). The treaty was finalised at a time of considerable political instability in Timor. It was not subject to the usual treaty review processes by the Australian Parliament, there being bipartisan criticism of the then Foreign Minister Alexander Downer’s haste to utilise a small window of opportunity for implementation of the treaty. In exchange for an increased share of the upstream revenue flow from any Sunrise development (increased from 18% to 50%), Timor agreed to Australia’s demand that they not refer any boundary dispute to a third party for settlement for 50 years.

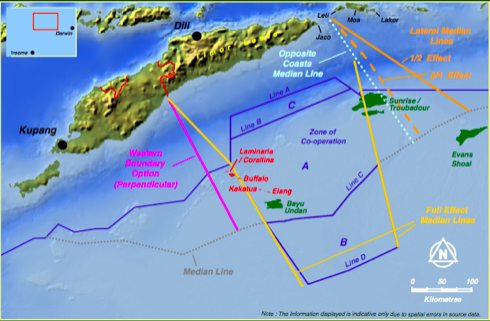

Timor-Leste already receives a steady revenue flow from the development of the Bayu Undan oil and gas field in the Timor Sea. It has a petroleum fund worth in excess of US$17 billion. Timor has employed leading international lawyers to advise on boundary delimitation. These lawyers have advised that Timor has a good case for establishing that the whole of Sunrise would fall within the Timor jurisdiction, being north of any median line (however modified to take account of varying length of coastlines) between the two countries, and being west of an adjusted equidistance line drawn by giving only 75% or less weight to the small Indonesian islands to the east of Timor-Leste. Professor Vaughan Lowe from Oxford had given a published opinion for another party to this effect as long ago as 2002.

Meanwhile, Australia’s lawyers continue to argue Sunrise is located under the Australian continental shelf, and that even if there be agreement on a median line between Australia and Timor, there would be little prospect of Timor getting any more than 20% of the upstream revenue flow because the Indonesian islands should be given their full weight when drawing the eastern equilateral line, in part because Indonesia is a classic archipelagic state. On the contrary, Timor could argue that though the baselines drawn for an archipelagic state may be relevant for determining archipelagic waters, they are not relevant when determining what weight to give to the small, isolated, and largely unpopulated islands which affect the drawing of an equitable line.

18 months ago, the joint venturers for the Sunrise project submitted their development proposal for a floating natural gas facility (FLNG), avoiding the need to pipe the gas to either Darwin or Timor. The Timorese leadership are not interested in an FLNG proposal which would yield no significant downstream revenue, would contribute nothing to the development of infrastructure in Timor, and would do little to assist Timor employment and training. There is a political imperative for the Timorese leadership to be able to deliver to their people an oil and gas project which develops tangible onshore benefits, and not just another offshore revenue flow like Bayu Undan. On the other hand, the Australian government supports the development of Greater Sunrise consistent with existing treaty arrangements including the requirement that the approved development plan reflect “best commercial advantage consistent with good field practice”. Australia thinks it in both countries’ interests that the fields be developed in accordance with commercial principles.

Armed with evidence of Australian spying on the Timorese during the negotiation of CMATS, the Timorese decided to challenge the validity of CMATS, commencing an international arbitration. Australia then conducted raids on premises which housed material relevant to the arbitration.

Under CMATS the determination of maritime boundaries is put on the long finger for 50 years while gasfields such as Sunrise are developed. Article 4.1 of CMATS provides: “Neither Australia nor Timor-Leste shall assert, pursue or further by any means in relation to the other Party its claims to sovereign rights and jurisdiction and maritime boundaries for the period of this Treaty.” But then again, the preamble of CMATS acknowledges that both parties are signatories to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and they need to take into account Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS “which provide that the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf between States with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law in order to achieve an equitable solution”. Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS both envisage that the parties might put in place provisional arrangements pending final delimitation but they specify that these arrangements are “not to jeopardise or hamper the reaching of the final agreement”. So it would be very difficult for Australia to argue that Timor-Leste should be prevented from seeking to initiate bilateral negotiations. Interestingly Article 4.7 of CMATS provides: “The Parties shall not be under an obligation to negotiate permanent maritime boundaries for the period of this Treaty.” So presumably the parties are still free to seek to negotiate maritime boundaries even during the period of the treaty; they’re just not obliged to.

The Timorese want to find an economically feasible way in which Sunrise can be exploited with the gas being piped onshore to Timor for processing. Unless that can be done, Timor has no interest in the short-term development of Sunrise. They think it is time to settle the boundaries. It’s time to pipe the gas to Timor, or to draw the line and get back to being good neighbours. Nothing is to be gained by Australia and Timor-Leste as neighbours airing dirty laundry in international fora. It’s time to find a political resolution of this issue.

Australia lost a significant case in the International Court of Justice in March 2014, when the Court ordered provisional measures in relation to the ongoing arbitration between Australia and Timor-Leste contesting the validity of CMATS. This case caused great embarrassment to Australia. The Timorese challenged Australia’s raid on the Canberra legal offices of one of their lawyers, Bernard Collaery, and on the home of witness K, a retired Australian intelligence officer. They asked that Australia return the seized materials. In May 2014, Mr Collaery informed the Australian Senate that he was acting as a lawyer for Witness K with the knowledge and approval of Ian Carnell, the Director General of Intelligence and Security. Collaery informed the Senate Privileges Committee: “Witness K alleged he had been constructively dismissed from ASIS, as a result of a new culture within ASIS. The evidence indicates that the change sought included an operation he had been ordered to execute in Dili, Timor-Leste.”

Back in March, the International Court of Justice ruled by 12 votes to 4 that Australia not use any of the seized materials from Collaery’s and K’s premises to the disadvantage of Timor-Leste and that Australia keep the seized documents under seal. The majority of judges were not satisfied that the undertakings by George Brandis QC, the Australian Attorney-General, were sufficient to safeguard Timor’s interests. Even some of the judges who found in Australia’s favour expressed some discomfort at what had occurred. For example, Sir Kenneth Keith from New Zealand said, “I regret that I cannot agree with two of the measures the Court has adopted. My regret is the greater for I do have some understanding of the ‘deep offence and shock’ felt in Timor-Leste about the actions of ASIO to which the Agent of Timor-Leste referred at the outset of this proceeding.”

Even more embarrassing for Australia was the court’s all but unanimous decision to order that Australia “not interfere in any way in communications between Timor-Leste and its legal advisers”. The decision was all but unanimous in the sense that the one Australian judge on the case was the only one to dissent from this order. Sir Christopher Greenwood, the UK judge, offered this damning indictment of Australia’s behaviour:

In view of the seizure of papers which clearly related to legal advice and preparation for the forthcoming arbitration from Timor-Leste’s lawyer, it is entirely understandable that Timor-Leste is concerned that there might be future interference and it sought an assurance from Australia that there would be no such interference. To my surprise, the undertaking from the Attorney-General makes no mention of this matter. In the absence of any undertaking not to interfere with Timor-Leste’s communications with its lawyers in the future, I accept that there is a real and imminent risk of such interference which requires action on the part of the Court.

The day after the decision was delivered, the Australian stable of Murdoch newspapers carried the headline: “Australia wins East Timor UN court fight”. This was no win for Australia; it was a humiliating defeat.

Timor-Leste then delivered its written pleadings for the hearing of the substantive case on 28 April 2014 and Australia in reply lodged theirs on 28 July 2014. On 1 September 2014, Senator Brandis told the Australian Senate:

It has been the policy of successive Australian governments that Australia should delimit its maritime boundaries through negotiations rather than resort to third-party dispute settlement, and that is the case here. You are also wrong, Senator Xenophon, in the suggestion that a median line is the only applicable principle. One thing your question ignores is the fact that the Australian continental shelf to the north-west of Western Australia runs beneath the Timor Sea very close to the southern coastline of East Timor. The median line principle, or the equidistance principle as it is sometimes referred to, is sometimes used, as the International Court of Justice affirmed in the North Sea continental shelf case in 1969 and again at the beginning of the Guinea-Bissau arbitration in 1986. It may be displaced by other circumstances.

This Australian approach fails take into account the developments in international law over the last 30 years of so. It fails to explain why it is that the Indonesians have still not ratified the 1997 treaty which establishes an exclusive economic zone and certain seabed boundaries for the two countries. There is a very credible case to be made that the Indonesians are anxious not to further cement their previously agreed continental shelf delimitation as they think it unjust. If Indonesia were negotiating a continental shelf boundary with Australia today, in all probability it would be drawn at or about the median line between the two countries.

That same day that Senator Brandis was repeating the time honoured Australian formula to the Senate, both governments submitted a request to the International Court of Justice to postpone the hearing of their substantive case which was to commence on 17 September 2014 “in order to enable them to seek an amicable settlement”. On 3 September, the court acceded to the request.

There is nothing to be gained for Australia and Timor as neighbours airing dirty laundry in such exalted international fora. It is time for both countries to agree to put the unresolved boundary issue to bed, seeking an agreement or determination by conciliation of the differences between them concerning the Timor Sea. The situation is similar to neighbours agreeing not to settle the boundary of their back fence. That is all very fine unless and until there is a problem. Once there is a problem, it makes good sense to determine the boundary. The boundary should be left unresolved only if there can be the assurance that both parties can get what they want in the meantime, living amicably as neighbours. The Timorese want to find an economically feasible way in which Sunrise can be exploited with the gas being piped onshore to Timor for processing. Unless that can be done, Timor has no interest in the short term development of Sunrise. They think it is time to settle the boundaries. It’s time to pipe the gas to Timor or to draw the line and get back to being good neighbours. That is the only route for finding “an amicable settlement”. This route would be consistent with what Senator Brandis described this month as “the policy of successive Australian governments”: “that Australia should delimit its maritime boundaries through negotiations”. When speaking of the Australia-Timor relationship, Australia’s Foreign Minister Julie Bishop has said, “The best is yet to come.” Her predecessor Alexander Downer is now High Commissioner to London. Back in 2006, he spotted a window of opportunity to accelerate the ratification of CMATS. Bishop now needs to bring a case to the Abbott Cabinet convincing them of the need to seize the moment for an amicable settlement by committing in the next few months to the negotiation of maritime boundaries with Timor-Leste. It would be the good neighbourly thing to do, and it would ensure that any dirty laundry is kept well out of the public international gaze. This could be good news for everyone on both sides of the Timor Trough.

Frank Brennan SJ AO is currently in the USA taking up the Gasson Chair at Boston College.

Frank Brennan SJ AO is currently in the USA taking up the Gasson Chair at Boston College.