‘In tropical climes there are certain times of day

When all the citizens retire to tear their clothes off and perspire.

It’s one of the rules that the greatest fools obey,

Because the sun is much too sultry

And one must avoid its ultry-violet ray…’

This comes from a satirical song from legendary writer and actor Noël Coward, in which he observes, from his 1932 perspective, that only Mad Dogs and Englishman go out in the midday sun. Nearly a century on, however, we’re far less inclined to crack wise about the elements when weather-related mortality seems closer than ever.

In March, Junaid Zafar Khan collapsed and died during a local cricket match in Adelaide, played in heat that soared above 40°C. A familiar face in the city's cricketing circles, Khan was remembered by friends as ‘a kind and generous person who enjoyed helping people’.

A death like Khan’s is not an isolated incident. The World Health Organisation estimates that nearly half a million people die each year from exposure to extreme heat. Late last year, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) reported on the state of the climate in Australia: ‘As Australia keeps warming, extreme heat events will become more frequent and more extreme. Extreme heatwaves cause more deaths in Australia than any other natural hazard.’

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), analysing data from 2012–2022, found that extreme heat accounted for 7104 injury hospitalisations and 293 deaths.

When the mercury rises dangerously high, it’s no longer simply a simple matter of discomfort. We know that hot days exacerbate mental health issues and social conflict. There is plentiful research to confirm heatwaves trigger an increase in ‘aggression, domestic violence, issues associated with mental and behavioural disorders — including self-harm — and mental health emergency presentations and hospital admissions’.

But when the seasons turn, maintaining a comfortable temperature is decidedly easier said than done.

Human beings through the centuries have had various attempts at keeping cool: Ancient Egyptians hung wet grass mats over their windows to cool the air through evaporation. Romans sipped snow-chilled drinks in public baths, their elite having snow carted down from the mountains and stored underground. Across the centuries, we’ve experimented with double-walled buildings, sea breezes, and passive cooling.

'Even when people have a roof over their heads, many have joined the ranks of the unemployed, the under-employed, the poverty-stricken, the financially-stressed and the marginalised. Many can no longer afford to run their cooling or heating, or to install effective units in the first place.'

In 1842, a U.S. physician named John Gorrie began cooling hospital rooms for fever patients, effectively paving the way for our use of modern refrigerators. And in 1901, engineer Willis Carrier installed the first modern electrical air conditioning unit in a New York publishing house. In 1906, the term ‘air conditioning’ was coined by Stuart Cramer of North Carolina, who added moisture to factory ventilation.

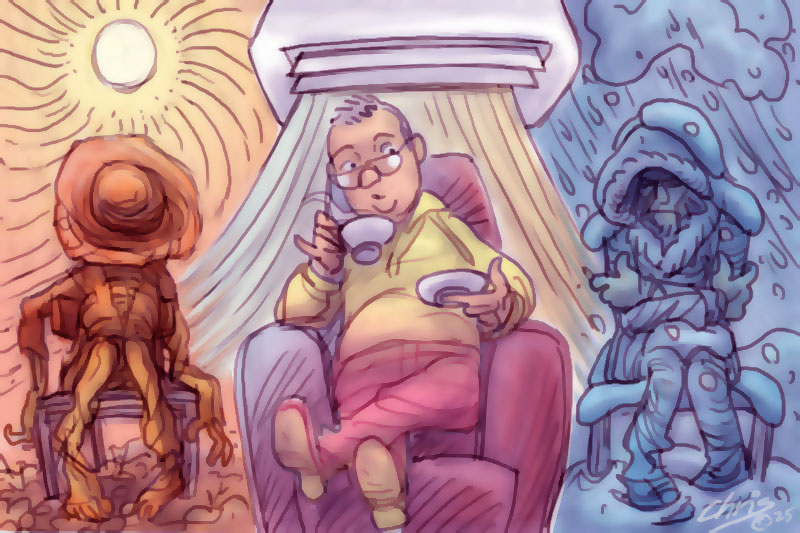

But here in Australia, in 2025, the ability to keep cool is still deeply unequal. We may live under the same searing sky, yet we are not all able to cope with its effects with the same capacity.

The ability to control the temperature of the air we breathe, sleep in, play in, work in and walk around in is a privilege, marked by gross inequity. For those without stable accommodation and the financial wherewithal to pay electricity bills (let alone install air conditioning, heating and split systems in the first place), that privilege remains out of reach.

The Victorian Council of Social Services (VCOSS) noted that heatwaves in 2009 and 2014 resulted in 374 and 167 ‘excess deaths’ respectively, with the indirect impacts of extreme heat including ‘mental illness, violence, financial stress, power outages, public transport disruptions, poor air quality, and service cancellations’.

Those ‘excess deaths’? They weren’t suffered by landlords or homeowners, but rather by people who were financially disadvantaged, on low or no incomes, often in poor-quality housing, or no housing at all.

The VCOSS report notes that Australia’s disadvantaged persons are likely to be more vulnerable to extreme heat yet are more likely to live in the areas of Melbourne where they are most exposed to it.

And while these immediate effects are already grim, the longer-term outlook is worse. A peer-reviewed study by a group of Australian universities has predicted that extreme heat may well double the impact of heart disease in Australia in the next 25 years, and ‘in a “severe scenario”, there could be a 182.6 per cent increase by 2050’.

There is no doubt that incidents of extreme weather are increasing.

And while we don’t suffer the extreme cold snaps of other nations in winter, fatalities from exposure to extreme cold are also rising in Australia. The AIHW notes that deaths ‘from injury due to extreme cold have risen gradually from 8 in 2015–16 to … 37 in 2020–21’, and that research ‘indicates people aged 65 years and older, and residents of major cities are at greater risk of death due to extreme cold’. Pensioners are well represented in the people I walk by each morning who sleep rough on Melbourne’s streets.

God help them, and God help us.

Much of the current political debate revolves around the cost-of-living crisis. Even when people have a roof over their heads, many have joined the ranks of the unemployed, the under-employed, the poverty-stricken, the financially-stressed and the marginalised. Many can no longer afford to run their cooling or heating, or to install effective units in the first place.

The Australian Council of Services (ACOSS) reported in March that half the people they surveyed were ‘skipping meals and going without medication to keep the air conditioning or heating on.’

But it’s the homeless who are most severely impacted. With no roof to sleep under, they have no access at all to heating or cooling, even on days when they desperately need it.

Knowing this truth and sharing it more broadly could encourage more Australian voters to push for a living wage to be introduced in this country. There is growing support for such a change. But the path forward is fraught with complex economic and political obstacles. In the meantime, those of us who are affluent, aspiring, or simply lucky enough to be housed, can turn up our collars against the coming winter and lament the rising cost of living from the comfort of our warm living rooms.

.

Barry Gittins is a Melbourne writer.

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.