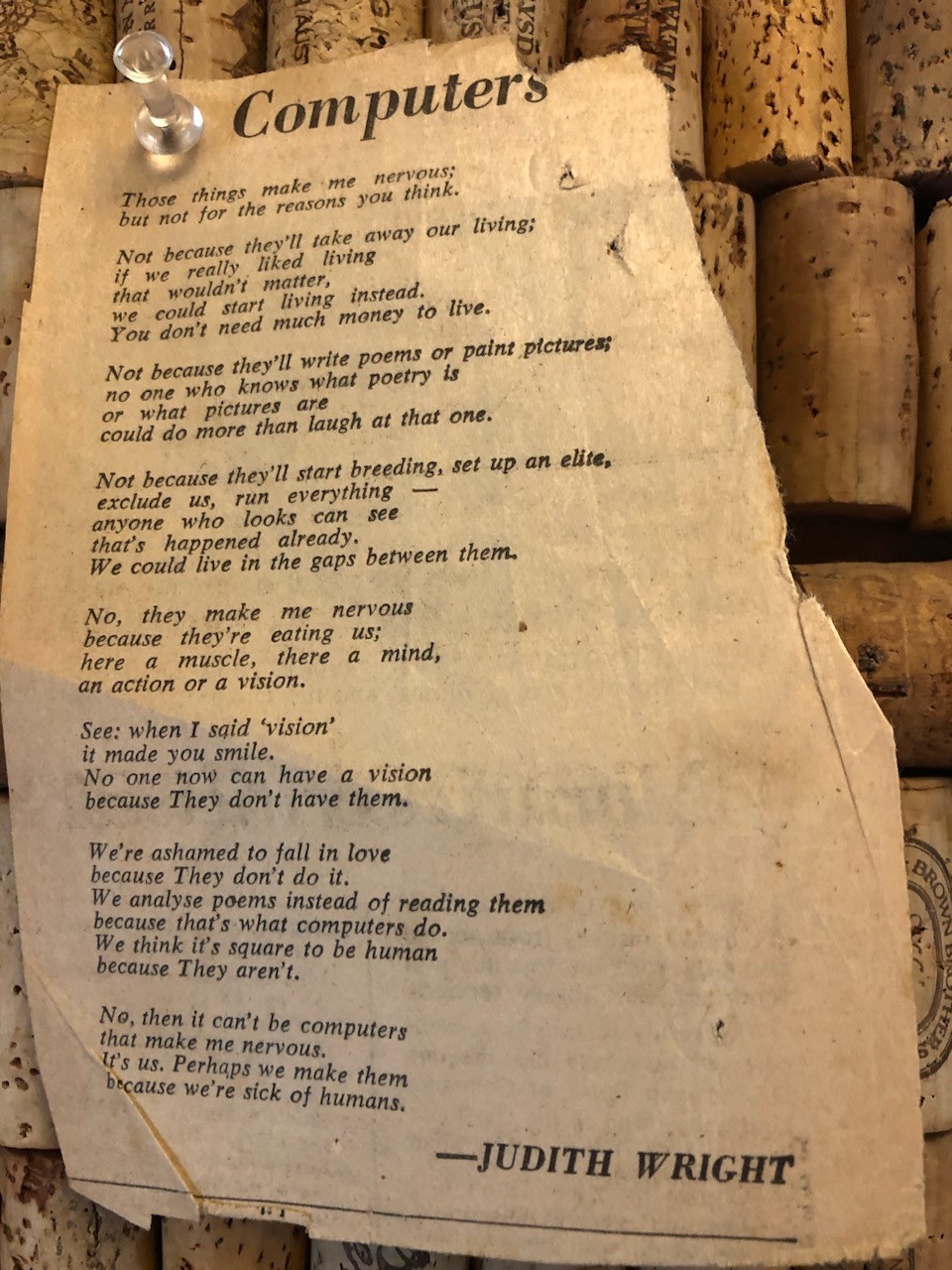

A scrunched, fading bookmark fell from a book. You don’t expect these things to drop out of something you picked up second-hand at a book fair. It was a cutting, a newspaper poem by Judith Wright entitled “Computers”.

Those things make me nervous

but not for the reasons you think,

she begins, setting up the dichotomy that our ways are not always a poet’s ways. Notice her connection of ‘things’ with ‘think’.

Not because they’ll take away our living;

if we really liked living

that wouldn’t matter,

we could start living instead.

You don’t need much money to live.

She raises this matter of ‘living’, which is about the most important subject in the world, more important than computers. She keeps in balance her rational mind, which says life is the ultimate value, with her emotional mind, influenced as it is by the unease engendered by the presence of computers. Notice how she introduces money from nowhere. She seems to be making a link between computers and money, one that today has become profound and universal. Things, like upgrades, passwords, and artificial intelligence are there because someone needed to prove they were possible; also, because they will make money for someone. Living, for Judith, is about creating, if we are to understand the next verse aright:

Not because they’ll write poems or paint pictures;

no one who knows what poetry is

or what pictures are

could do more than laugh at that one.

This is a confident assertion of the originality of human creation, made with a certainty based in experience. Laughter, by implication, is not a computer’s forte. To exist inside the living place of our life is to be able to see the absurdity of a world contingent on inanimate machines. Our sentient selves, fully capable of abstract thought as of emotional responses, makes our expressions personal. They are the reality of our lived experience in ways computers cannot say. The need for genuine communication, for relationship outside our solitary selves, drives the creative act. She then turns her gaze to society and politics, as was oft her wont:

Not because they’ll start breeding, set up an elite,

exclude us, run everything –

anyone who looks can see

that’s happened already.

We could live in the gaps between them.

Judith doesn’t describe these gaps, though we can intuit plenty of them in the lines of the poem. Instead, we have reached halfway, which is where she turns to the true explanation of her nervousness.

No, they make me nervous

because they’re eating us;

here a muscle, there a mind,

an action or a vision.

As elsewhere, she moves quickly from the particular to the immensely general, invoking in spare lines an incipient negative mood formed by computers.

See: when I said ‘vision’

it made you smile.

No one now can have a vision

because They don’t have them.

Her conversational mode works to take us into her confidence. She trusts the human responses of smiling and questioning, and other attributes where a computer falls short. It is in these small involuntary reactions of our physical being that Judith Wright feels at home. Humour saves any amount of time. Then, having taken us into our confidence, she goes up several registers:

We’re ashamed to fall in love

because They don’t do it.

We analyse poems instead of reading them

because that’s what computers do.

We think it’s square to be human

because They aren’t.

Actually, it’s most computers that are square (literally), not humans. But we grasp her meaning, computers are some irresistibly cool invention we tell ourselves we cannot do without. As though they know something that we don’t. ‘Square’ is the only word that dates Judith’s poem, which googling reveals was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 18th of June 1966. Computers were big in those days, with sharp edges and corners.

So, having assessed the advent of computers, in a poem that bears our close analysis, the poet does a fresh turn of thought, leaving us fairly much squarely where computers started, the root cause of the problem:

No, then it can’t be computers

that make me nervous.

It’s us. Perhaps we make them

because we’re sick of humans.

I smile and pin Judith’s poem on the corkboard for further consideration. At the very least, the poem seems an exhortation to spend more time attending to others, and to what it is that makes us human. It is a refutation of the computer’s purported claims to omniscience, a declaration that we will not be dumbfounded by computers, a gentle gesture designed to put computers firmly in their place in the scheme of things.

Main image: Supplied.