I join with Fr Bill Uren and Sean Burke in welcoming you here to Newman College (pictured right). Until 100 years ago, this place where we meet was still an open paddock. It was the traditional land of the Wurundjeri people who had made their home here as hunters and gatherers for tens of thousands of years. The surrounding blocks were already the sites for the splendid university colleges erected by the other major Christian Churches with a presence here at the University of Melbourne. You will understand that the Catholics, many of whom were Irish, did not yet have the means nor the vision for the building of their own college on the crescent adjacent to the university.

I join with Fr Bill Uren and Sean Burke in welcoming you here to Newman College (pictured right). Until 100 years ago, this place where we meet was still an open paddock. It was the traditional land of the Wurundjeri people who had made their home here as hunters and gatherers for tens of thousands of years. The surrounding blocks were already the sites for the splendid university colleges erected by the other major Christian Churches with a presence here at the University of Melbourne. You will understand that the Catholics, many of whom were Irish, did not yet have the means nor the vision for the building of their own college on the crescent adjacent to the university.

International visitors need to appreciate that Sydney was founded well before Melbourne with the result that there was already a well established Catholic men’s college at the University of Sydney. But not even Sydney had a college for Catholic women. Back in 1885, Cardinal Moran had cause to dismiss the then rector of Sydney’s St John’s College for ‘levity of conduct with young ladies’ as well as for low enrolments. I don’t know how sustainable the rector’s claim on his job would have been if enrolments had been healthier. When looking for a new college rector, Cardinal Moran could not afford to be too choosy. But he did rule out two classes of men: Englishmen and Jesuits. He regarded Jesuits as ‘a law unto themselves’.

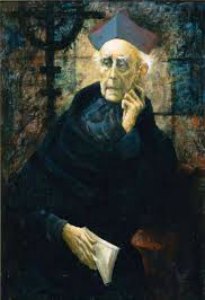

When the legendary Irish cleric Daniel Mannix (pictured below) left Maynooth and came here to Melbourne as coadjutor bishop to Archbishop Carr in 1913, Carr entrusted him with the mission of developing this vacant site. Brenda Niall, a splendid Australian biographer, has recently published a new life of Mannix. She was left in no doubt that Mannix had no interest in building a Catholic university, but rather saw the need for Catholics in the tertiary education sector to act as a leavening element in the thoughts and ideals of the developing secular universities. Unlike many other countries, Australia has long had a strong system of Catholic secondary schools but until recently no Catholic universities. I remember when the Provost of the newly established Notre Dame University here in Australia proudly told my father when he was Chief Justice of Australia that Notre Dame was about to establish Australia’s first Catholic law school. Dad simply responded with a question, ‘Must you?’ We now have two Catholic universities in Australia. Much has changed since Mannix’s day.

In a chapter entitled, ‘Playing Poker with the Jesuits’, Brenda Niall spells out Mannix’s vision for Catholic tertiary education. He wanted to put Catholics (and that more than often meant Irish) ‘on a footing similar to that of other denominations’. In 1910, Archbishop Carr had welcomed the Newman Society into his archdiocese so that it might have a presence here at the University of Melbourne. Brenda Niall opines that nothing much might have become of Mannix but for the 1916 Easter uprising at the post office in Dublin and the subsequent conscription campaigns here in Australia where Mannix strongly and successfully opposed government moves for military conscription during the First World War.

Planning for Newman College, Mannix, unlike his Sydney episcopal brethren, wanted the Jesuits to do the job. It would have made sense for him to commission Fr James O'Dwyer SJ, then rector of Xavier College, our large Jesuit secondary school with place for boarders, to be the first rector. But alas, though Irish born, O'Dwyer was ‘a King and Empire Man’ who had told the Old Xaverians at the outbreak of the war that ‘in the story of Empire there is nothing so unselfish as the relation of the Motherland to her colonies’. This was too much for Mannix. Eventually he found another Jesuit for the task.

Once assured a major donor from Sydney, Mannix took a very hands on approach to the construction of Newman College. He knew that architecture mattered. He made a bold choice, giving the job to an American couple Walter Burley Griffin and his wife Marion Mahony. Brenda Niall observes that Mannix ‘never liked being predictable and it would have pleased him to have the Catholic college, a latecomer to the University of Melbourne, make such a strong statement of individuality. Choosing between adventurous modernism and predictable neo-Gothic, Mannix would take the risk of the new, even at the cost of antagonising the major donor.’

You will note that we are gathered in the splendid circular dining room. Thomas Donovan, the Sydney donor, disliked much about the building, but most especially this dining room. He thought it was designed to ‘enforce equality’. That was the sort of thing Americans did! It was American, even socialist, in feeling. Niall interprets Donovan’s displeasure: ‘No humble approach to High Table, no dignity, nothing to signal the authority of the rector’. Mannix was so delighted with the result that he became a great backer for Burley Griffin who then became the architect for Canberra, our national capital which is home for me and Newman’s erstwhile rector Fr Peter L’Estrange. I often tell my American friends that Canberra is a bit like Washington DC, but without the power, money, influence and prestige.

On the far wall you will see the portrait of Fr Jeremiah Murphy who was rector here for 30 years. He loved the place, and he was very at home engaging with the administration of the University of Melbourne. When his provincial finally moved him to Xavier College, he wrote in his diary: ‘Entered the desert’. He died within a year, aged 71.

As a young Jesuit, I had a couple of brief stints here at Newman, tutoring in constitutional law. Kevin Andrews who is now the Australian Minister for Defence was president of the students’ club. Kevin is part of a cabinet which contains a great number of alumni from Jesuit schools including the Prime Minister, the Treasurer, the Minister for Finance, the Minister for Education and the Minister for Agriculture. And it almost goes without saying that the nation’s Chief Justice and Leader of the Opposition also attended Jesuit schools. It’s good for our corporate humility to acknowledge that the Governor-General was educated by the Christian Brothers and that our Queen received no Catholic education at all, though she is of course not one of us, and she lives on the other side of the globe.

I suspect Pope Francis had some of our alumni in mind when he wrote in his encyclical Laudato Si:

A politics concerned with immediate results, supported by consumerist sectors of the population, is driven to produce short-term growth. In response to electoral interests, governments are reluctant to upset the public with measures which could affect the level of consumption or create risks for foreign investment. The myopia of power politics delays the inclusion of a far-sighted environmental agenda within the overall agenda of governments. Thus we forget that “time is greater than space”, that we are always more effective when we generate processes rather than holding on to positions of power. True statecraft is manifest when, in difficult times, we uphold high principles and think of the long-term common good. Political powers do not find it easy to assume this duty in the work of nation-building.

Many of us were last gathered together five years ago in Mexico at this conference under the leadership and inspiration of the late Fr Paul Locatelli SJ to hear Fr General Adolfo Nicolas put before us three major challenges in response to what he called the pervasive ‘globalisation of superficiality’ by which we can be ‘overwhelmed with such a dizzying pluralism of choices and values and beliefs and visions of life, then one can so easily slip into the lazy superficiality of relativism or mere tolerance of others and their views, rather than engaging in the hard work of forming communities of dialogue in the search of truth and understanding’. Fr General told us:

Many of us were last gathered together five years ago in Mexico at this conference under the leadership and inspiration of the late Fr Paul Locatelli SJ to hear Fr General Adolfo Nicolas put before us three major challenges in response to what he called the pervasive ‘globalisation of superficiality’ by which we can be ‘overwhelmed with such a dizzying pluralism of choices and values and beliefs and visions of life, then one can so easily slip into the lazy superficiality of relativism or mere tolerance of others and their views, rather than engaging in the hard work of forming communities of dialogue in the search of truth and understanding’. Fr General told us:

First, in response to the globalization of superficiality, I suggest that we need to study the emerging cultural world of our students more deeply and find creative ways of promoting depth of thought and imagination, a depth that is transformative of the person. Second, in order to maximize the potentials of new possibilities of communication and cooperation, I urge the Jesuit universities to work towards operational international networks that will address important issues touching faith, justice, and ecology that challenge us across countries and continents. Finally, to counter the inequality of knowledge distribution, I encourage a search for creative ways of sharing the fruits of research with the excluded; and in response to the global spread of secularism and fundamentalism, I invite Jesuit universities to a renewed commitment to the Jesuit tradition of learned ministry which mediates between faith and culture.

Those of us inspired by the Jesuit tradition once again gather in the global South to consider the challenges put to us by Fr General. We mourn the loss of Paul Locatelli who died soon after our last conference reminding us: ‘We must challenge the illusion of privilege and isolated individualism. We must bind ourselves emotionally and functionally to others and to the earth.’ This time we have gathered in Asia, though admittedly Australia is probably the least Asian country in South East Asia. Fr Peter Pham the Georgetown theologian recently reflected on the Church in Asia which he describes as ‘the cradle of the world’s religions’. Profiling the concerns of the Federation of Asian Bishops Conference, Pham writes:

The FABC’s dominant concern is centred on the kingdom of God (not on the institutional church); mission (not inward-self-absorption); communion (not splendid isolation); dialogue (not imperialistic monologue); solidarity with victims (not victim-blaming and withdrawal into an otherworldly ‘spirituality’); care of creation (not exploitation of natural resources); and witness/martyrdom (not cowardly compromise).

We are now preparing for the 36th General Congregation of the Jesuits. And we are buoyed up by the leadership of our Jesuit pope Francis who embodies so much of what we espouse and who challenges us to respond with full hearts, applied minds, and willing hands.

Remember how Pope Francis ended his address to the journalists in Rome on the day after his election when he gave a blessing with a difference. He said:

I told you I was cordially imparting my blessing. Since many of you are not members of the Catholic Church, and others are not believers, I cordially give this blessing silently, to each of you, respecting the conscience of each, but in the knowledge that each of you is a child of God. May God bless you!

Now that is what I call a real blessing for anybody and everybody—and not a word of Vaticanese. Respect for the conscience of every person, regardless of their religious beliefs; silence in the face of difference; affirmation of the dignity and blessedness of every person; offering, not coercing; suggesting, not dictating; leaving room for gracious acceptance. These are all good pointers for us members of the Jesuit Higher Education Network holding the treasure of the Ignatian tradition, Roman authority and Catholic ritual in trust for all people of good will, including all our staff and students, as we discern how best to make a home for God in our lives and in our world, assured that the Spirit of God has made her home with us.

Something crystallised for me at the splendid Sydney Opera House soon after the election of Francis when I appeared on stage with the British philosopher AC Grayling, author of The God Argument, and Sean Faircloth, the US director of one of the Dawkins Institutes passionately committed to atheism. We were there to discuss their certainty about the absurdity of religious faith. Mr. Faircloth raised what had already become a hoary old chestnut, the failure of Pope Francis when provincial of the Jesuits in Argentina during the Dirty Wars to adequately defend his fellow Jesuits who were detained and tortured by unscrupulous soldiers. Being a Jesuit, I thought I was peculiarly well situated to respond. I confess to having got a little carried away. I exclaimed: Yes, how much better it would have been if there had been just one secular, humanist, atheist philosopher who had stood up in the city square in Buenos Aires and shouted, ‘Stop it!’ The military junta would have collectively come to their senses, stopped it, and Argentinians would have lived happily ever after. The luxury for such philosophers is that they never have to get their hands dirty and they think that religious people who do are hypocrites unless of course they take the course of martyrdom. As believers, we are able to hold together ideals and reality, commitment and forgiveness.

Last November, I had the good fortune to be a visiting professor at Boston College where the university community marked the 25th anniversary of the assassination of the six Jesuits, their housekeeper and her daughter at the Universidad Centroamerica (UCA) in El Salvador during their dreadful civil war. The American poet Carolyn Forché who spent years in El Salvador listening to the horrific stories addressed us. She spoke about ‘A Poet’s Journey from El Salvador to 2014: Witness in the Light of Conscience’. She knew Fr Ignacio Ellacuria SJ, the rector of UCA who was the main target of the assassins. He taught her that ‘each moment of our life shapes the whole of our life, and that we are not always responsible for what befalls us but we are certainly responsible for our response’. He spoke of the capacity to meet the moment beautifully, and in a manner that honours our deepest human aspirations.

She was a friend of the late, now canonised, Archbishop Oscar Romero. She was with him the week before he was assassinated in March 1980. This is how she told the story:

I met with Monsignor in the kitchen of the convent of the Carmelite Missionary Sisters, where he told me gently that it was time for me to go home, as the situation had become too dangerous, and I was more needed in the United States, in the work of helping Americans to understand the struggle for justice. But I begged him to leave, as his was the first name on the death squads’ lists. He seemed so calm that afternoon, tapping his fingers on the Bible he carried with him. I realised I was in the presence of a saint. ‘No’, he said, ‘my place is with my people, and now your place is with yours.’

In the Boston audience was Fr Donald Monan SJ who had been president of Boston College when his Jesuit brothers at his sister university were assassinated. With other Jesuit university presidents from the USA, he went to El Salvador and sat through the trial of the soldiers indicted with the killings. He spent years lobbying US congressmen to withdraw support for the unaccountable military in El Salvador, observing, ‘The intellectual architects of this crime have never been publicly identified’ or called to account.

When Ellacuria became rector of UCA he said that his country was ‘an unjust and irrational reality that should be transformed’ and that the university needed to contribute to social change: ‘It does this in a university manner and with a Christian inspiration.’ When Monan returned from El Salvador, he was fond of telling his students: ‘We must do all we can to ensure that freedom predominates over oppression, justice over injustice, truth over falsehood, and love over hatred. If the university does not decide to make this commitment, we do not understand what validity it has as a university, much less as a Christian inspired university.’

The voice of conscience missions the believer not just for service in the Church but most especially for service in the world, not just with commitment to justice in the Church but most especially to justice in the world. This cannot be done without a commitment to laws and policies which do justice, protecting the weak and vulnerable. It is a call to take an intelligent, informed stand in solidarity. In his encyclical Pope Francis calls us to consider the tragic effects of environmental degradation especially on the lives of the world’s poorest. He says:

The problem is that we still lack the culture needed to confront this crisis. We lack leadership capable of striking out on new paths and meeting the needs of the present with concern for all and without prejudice towards coming generations. The establishment of a legal framework which can set clear boundaries and ensure the protection of ecosystems has become indispensable, otherwise the new power structures based on the techno-economic paradigm may overwhelm not only our politics but also freedom and justice.

Developing the culture, the leadership, and the legal framework. These are the challenges to those of us who want to be intelligent believers responding to the call of the Spirit. It is heartening to note the pope’s humility born of true consultation with bishops’ conferences (17 of which are quoted directly in the encyclical) and detailed meetings with experts including scientists, economists and political scientists as well as philosophers and theologians. Having noted, ‘There are certain environmental issues where it is not easy to achieve a broad consensus’, he concedes that ‘the Church does not presume to settle scientific questions or to replace politics. But I want to encourage an honest and open debate, so that particular interests or ideologies will not prejudice the common good’.

Returning home to our universities and places of higher learning, we must commit all our institutions to engagement in this honest and open debate, respecting the competencies of all, and inspired by Pope Francis’s vision of St Francis of Assisi who is the model of “the inseparable bond between concern for nature, justice for the poor, commitment to society, and interior peace”. Mind you, I do think the encyclical would be all the stronger if it conceded that the growth in the world’s human population - from 2 billion when Pius XII first spoke of contraception to 3.5 billion when Paul VI promulgated Humanae Vitae to 7.3 billion and climbing as it is today - points to a need to reconsider the Church’s teaching on contraception. The pope is quite right to insist that the reduction of population growth is not the only solution to the environmental crisis. But it is part of the solution. It may even be an essential part of the solution. Banning contraception in a world of 7.3 billion people confronting the challenges of climate change and loss of biodiversity is a very different proposition from banning it in a world of only 2 billion people oblivious of such challenges.

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of Vatican II and preparing for the forthcoming Synod on the Family, we can take heart from the changes in our Church which permit and encourage such questions and dialogue. You will note that one effect of the recent encyclical is that it is no longer just liberal Catholics who are labeled as cafeteria Catholics. Some erstwhile conservative Catholics and papal apologists have become very exceptionalist in their discussion of this encyclical. We are now all welcome to the real world of questioning engagement in a Church that we cherish for its teaching office and sense of tradition. John O'Malley SJ, the finest contemporary historian of Vatican II writing in the English language has provided us – in his contribution to the Continuum 2007 collection Vatican II: Did Anything Happen? – with ‘a simple litany’ of the changes in church style indicated by the council's vocabulary: ‘from commands to invitations, from laws to ideals, from threats to persuasion, from coercion to conscience, from monologue to conversation, from ruling to serving, from withdrawn to integrated, from vertical and top-down to horizontal, from exclusion to inclusion, from hostility to friendship, from static to changing, from passive acceptance to active engagement, from prescriptive to principled, from defiant to open-ended, from behaviour modification to conversion of heart, from the dictates of law to the dictates of conscience, from external conformity to the joyful pursuit of holiness.’

As members of the Jesuit Higher Education Network committed to social justice we have great potential and vast material, intellectual and spiritual resources. But this is no time for self-satisfaction nor complacency. If you’re in any doubt about that, consider only this week’s London Tablet which carries the front page headline: ‘Are the Jesuits pulling out of Britain?” The closure of Heythrop College brings to an end a history that began in Louvain in Belgium in 1614, when it was illegal to educate Catholic priests in England. The original college in Louvain was made possible by the gift of a wealthy English benefactor. Four centuries later, its successor institution has now run out of benefactors. No institution is sacred. No institution is spared the scrutiny of accountants and bean counters.

Looking to the future, lets sustain each other in hope. Looking to the future, I conclude appropriately quoting one of our fine contemporary women theologians. In her new book Ask the Beasts: Darwin and the God of Love, Elizabeth A Johnson, writes: ‘Living the ecological vocation in the power of the Spirit sets us off on a great adventure of mind and heart, expanding the repertoire of our love.’ Let’s leave the Newman dining room this evening grateful for the vision of Mannix, inspired by the architecture of the Griffins, buoyed by the encyclical of our Jesuit pope, and grounded in the realities that all this needs to be translated into the daily fare of fee paying education for students seeking employment in a globalised world back home.

This is the text of an address titled 'Expanding the Jesuit Higher Education Network: Collaborations for Social Justice', delivered at the Jesuit Higher Education Conference, Newman College, University of Melbourne on 8 July 2015.