The climate crisis may be ever more urgent but climate diplomacy runs according to schedule. After three decades of well-established routine, international climate talks have acquired their own seasonality. The tone for the new year is set by the meeting of the Conference of Parties (COP) held in the last weeks of the year just gone. 2024 has therefore started in the shadow of two weeks of intense negotiations held in a vast expo campus in the desert outside Dubai.

COP28 in Dubai was a milestone in several respects – not just for the consensus language on transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems that emerged from the extended ministerial negotiations in the conference’s last days and has dominated headlines. For instance, the agreement of a new fund for responding to climate loss and damage capped decades of advocacy by vulnerable nations and NGOs. This was also the moment when the international community began grappling with what AI means for climate change.

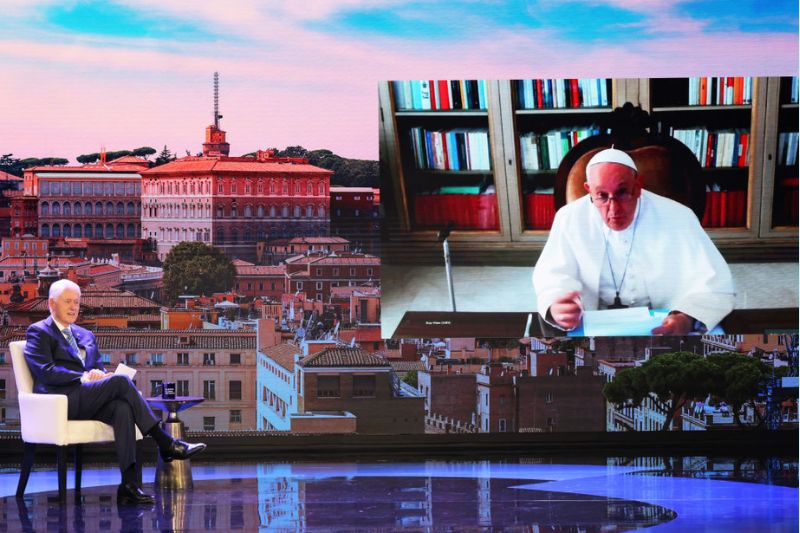

One milestone did not come to pass. COP28 was to have been the first COP attended by a pope. While Pope Francis had been due to participate in the session for heads of state or government, he cancelled his trip on medical advice days before the COP began. But if the pope was unavoidably absent, the Holy See was very much present. Under Francis’ leadership, the Holy See joined both the UN Climate Convention and the Paris Agreement, accepting obligations under these treaties and giving the Vatican the right to participate in decision-making.

Weeks before COP28, the Vatican published Francis’ apostolic exhortation Laudate Deum, addressed to ‘all people of good will on the climate crisis’. Rather than attempt to evaluate the (probably modest) impact of Laudate Deum (LD) on COP28, I would like to comment on LD as reflecting a strengthening current in climate politics, namely a focus on justice in climate responses.

The Pope framed LD as a follow-up to his 2015 encyclical, Laudato Si’ (LS). LS was, by design, a powerful intervention in climate politics: a pope writing at length on climate change and related ecological problems, urging action. The French environment minister at the time of the 2015 Paris conference, Ségolène Royal, has recalled how Francis responded to her suggestion that LS be fast-tracked for publication before the COP21 conference: ‘In front of me, he called the Vatican! And I heard him say, ‘…We absolutely must speed things up, and as soon as I get back to the Vatican, I want to see where you are at.’ I was stunned. And the encyclical was published before COP21’.

LS contributed to the groundswell of momentum that resulted in the Paris Agreement. In the years since, it inspired a new civil society coalition and led the Vatican to adopt a set of ‘Laudato Si’ Goals’ (which also seem partially modelled on the troubled Sustainable Development Goals). These goals are prompting action in various parts of the Catholic world, including in Australia. LS remains a profound document, equal parts meditation and action agenda.

Laudate Deum is very different. It opens with the Pope’s reflection that in the years since the publication of LS, ‘I have realized that our responses have not been adequate, while the world in which we live is collapsing and may be nearing the breaking point’. Therefore, Francis continues, the ‘reflection and information that we can gather from these past eight years allow us to clarify and complete what we were able to state some time ago’.

'The only durable pathways to the Paris goals are those that make space for the most vulnerable countries and the most vulnerable people within countries.'

Having clearly decided that more needed to be said, Francis likely confronted a challenge familiar to the authors of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and other scientific experts that regularly warn their fellow humans about the climate crisis: how to get the attention of people who may have become numb to such warnings without feeding climate ‘doomism’. Unlike Spinal Tap’s amp, which goes to 11, there is no obvious way to escalate climate messaging in this context.

Francis’ approach is to speak in direct – sometimes blunt – terms about the shortcomings of climate action in recent years. For instance, he highlights the gaps in per capita greenhouse gas emissions between the United States, China and ‘the poorest countries’. Inequality is at the heart of the climate problem, which is ‘a global social issue and one intimately related to the dignity of human life’. For Francis, solutions cannot be found in a ‘growing technocratic paradigm’ that promotes the illusion of unlimited human power and wealth, but rather in a reconfigured and democratised multilateralism that can provide for ‘global and effective rules’.

Laudate Deum reads like an unfiltered statement of concern. Some of its assertions are contestable (e.g. that ‘the climate crisis is not exactly a matter that interests the great economic powers’) or inaccurate (namely, that the Kyoto Protocol’s 2012 goal was ‘not achieved’). La Croix has reported that LD ‘was never submitted to review by the [Vatican] Secretariat of State before its publication’. Perhaps some polish was sacrificed to speed.

Far more importantly, Francis’ latest interventions are in sync with a growing policy focus on climate inequalities. In his statement to COP28 (read by Cardinal Parolin), Francis stated that ‘the poor are the real victims of what is happening’. It has become extremely hard to disagree. In fact, when it comes to climate justice, a growing number of policymakers are on the same page as the Pope.

At the international level, this can be seen in some of the COP28 outcomes. The new loss and damage fund’s purpose is to ‘assist developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change’. Negotiators also agreed that a work programme on ‘just transition’ would include a focus on ‘decent work and quality jobs’. Just Transition Energy Partnerships with individual developing countries (such as Indonesia) seek to accelerate decarbonisation in a socially cohesive manner. Other agendas, such as reform of multilateral development banks, aim to ramp up climate financing without adding to crippling indebtedness.

Domestically, a growing number of countries and states are adopting policies to address the social dimensions of the climate transition. Just transition is also on the agenda in Australia, at least within the union movement and civil society.

This turn to addressing at least some aspects of climate justice in the years following the Paris Agreement is unlikely to be the result of a ‘a sudden revolution in human nature’. It more likely reflects dawning recognition, both at the level of international, consensus-based negotiations and within democracies, that the carbon books cannot be balanced on the backs of the poor. The only durable pathways to the Paris goals are those that make space for the most vulnerable countries and the most vulnerable people within countries. In 2024 – the 800th anniversary, as Pope Francis reminds us, of Francis of Assisi’s ‘Canticle of the Creatures’ – it is vital to step up the practical work of climate justice.

Dr Stephen Minas is a member of the UN Climate Technology Executive Committee.

Main image: Bill Clinton and Pope Francis have a conversation during the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) meeting on September 2023 in New York City. (Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images)