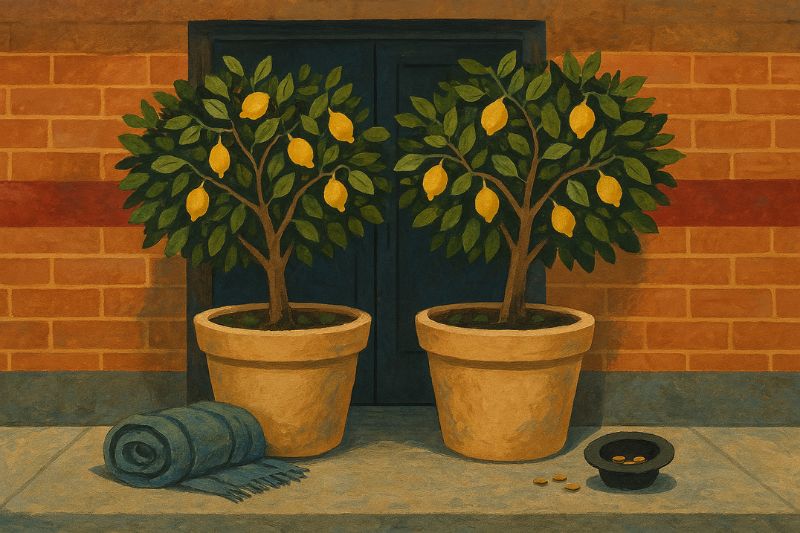

A few weeks ago in Fremantle, a pair of lemon trees in oversized pots appeared in the alcove of a shuttered storefront on a popular shopping strip. But rather than being ornamental, these pots had been strategically placed to block access to a doorway where homeless people had been sleeping.

At first glance, this quirky response to rough sleepers might seem relatively benign. But this small act of urban cruelty is just another example of policy of obstruction in urban design, known as ‘hostile architecture’, which often target homeless people to restrict their access to public spaces, and prevent them from getting even sporadic rest.

Across Australia, such tactics are becoming more common, and once you see it, you see it everywhere. The benches with armrests, or strips of metal that prevent lying down, or spikes embedded into concrete. It’s a worldview that seeks to regulate public space by excluding the inconvenient. And at its heart is a moral inversion where compassion becomes weakness. A park bench becomes contraband if a rough sleeper sleeps on it, and a lemon tree becomes a wall.

It reflects a wider anxiety about homelessness, and a desire of wealthy cities to preserve an illusion of prosperity by rendering the suffering of the poor invisible.

In Melbourne, the City of Port Phillip has proposed new laws that would criminalise rough sleeping, ostensibly to address drug-related crime. The new statutes would allow for fines and penalties against people who, in effect, have nowhere else to go. Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan called it a decision that ‘lacks compassion for our vulnerable Victorians,’ and has urged the council to reconsider its proposal, which awaits a report due in May.

And in Brisbane only a few weeks ago, homeless people were forcibly evicted from public parks, apparently in the name of public safety.

Forcibly removing homeless people is a strategy that is regularly deployed prior to major and international sporting events. In the lead-up to the Atlanta Olympics in 1996, and the Sydney Olympics in 2000, rough sleepers were removed from public spaces in city centres. In New Orleans, ahead of this year’s Super Bowl, homeless encampments were dismantled in what officials described as an effort to improve ‘public amenity.’ Similarly, in Rio during both the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, favela residents were displaced to make room for stadiums and sidewalks deemed more camera-friendly.

Cities paradoxically celebrated for their ‘liveability’ are becoming increasingly unliveable for the most vulnerable people.

'If you lock someone out from supports, leave them to suffer by themselves, then it’s a short path until they’re locked up. As communities, we need to lock people in, giving them what they need to survive, not lock them up.'

These are just the most recent manifestations of a deeper civic impulse to retreat from empathy in the face of complexity, emerging from a simmering anger that crops up time and again towards people who are homeless.

‘Where does this anger towards homeless people spring from?’ I asked a bloke who has been helping homeless people and advocating for them for decades.

Brendan Nottle, a longtime Salvation Army officer based in Melbourne’s CBD, has seen this up close. ‘We are living with economic uncertainty and pain, and people are looking for someone or something to blame,’ he says. ‘They see homeless people and say, “They’re the reason why I’m struggling; why no-one is accessing my business.”’

Brendan speaks from decades on the street, from conversations over shared meals, from funerals attended for people whose names were forgotten by the systems that failed them. (In 2017 he publicly advocated on behalf of homeless people who had been moved on from the CBD before the Australian Open.)

‘The proposal to criminalise homelessness is a form of apartheid. It identifies a group of people and says, “They aren’t going to be welcome here. Someone needs to get rid of the homeless”.’

When fear and anger spur action, people look to render homeless people not only invisible but illegal. Brendan explains that, with the weary weight of long-held perception, ‘they focus on what presents before them rather than what’s beyond them’.

‘We have to look beyond the scruffy clothes, and past the urine-soaked cardboard they sleep on; we have to listen to their story to realise how they got to where they are. They did not choose their pain. They did not choose to be homeless, but they are victims of their circumstances.

‘Rather than give people our judgment, let’s give them our compassion.’

‘Somewhere it has to stop,’ Brendan told me, recalling the words of his late friend, Father Bob Maguire. ‘We have a spiritual legacy in Melbourne. no-one is left behind; we bring the outsider in; and we challenge the structures and conditions that alienate people and produces victims.’

In those early days of European incursion, Brendan explains, John Batman was driven by commerce. But one of Batman’s fellow settlers, Henry Reed, who’d loaned £3000 to Batman to establish the settlement that became known as Melbourne, was driven by his Methodist beliefs and world view. Reed also made connections with the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation, the traditional owners of the Yarra River Valley; they shared a compassionate and inclusive view of life. Later in his life, Reed contended that he’d preached the first sermon in Melbourne, which was attended by Batman, William Buckley and three Aboriginal Australians hailing from Sydney.

Melbourne has a legacy of including the outcast, and addressing the reasons why they were ‘cast out’ in the first place. But that legacy, he warns, is at risk.

The push to make being homeless a crime has also been accompanied by reportage that homelessness is interlinked with crime and that, in the city of Port Phillip, crime is the ‘worst it’s been in 35 years’.

Brendan suggests that any consideration of the intersection between crime and homelessness must also examine hunger, thirst, addiction, unemployment, mental and physical health issues, family and domestic violence, abuse, despair and loneliness.

‘We have to be careful as a society,’ Brendan says. ‘If you lock someone out from supports, leave them to suffer by themselves, then it’s a short path until they’re locked up. As communities, we need to lock people in, giving them what they need to survive, not lock them up.’

Another regular complaint made against homeless people is that they sometimes have accommodation yet do not use it. This fails to recognise the complexity of life for those who sleep rough (a roof over someone’s head does not magically or automatically resolve homelessness), and their need for community and mateship.

‘Responses during COVID-19 and the lockdowns, with emergency accommodation and long-term housing pursuits, decreased rough sleeping numbers here in Melbourne,’ Brendan says. ‘But in our rush to get people into housing, we didn’t unpack and address the drivers that lead people into living and sleeping rough.’

Brendan is concerned that there is ‘a risk of homelessness significantly increasing’, both in Melbourne and throughout Australia. He and his colleagues are seeing rising numbers of people who are battling increasing cost-of-living pressures.

‘We see men and women trying to deal with food insecurity, with rising rents or mortgages,’ he explains. ‘That kind of stress can lead to mental health issues, to family violence, to unemployment and the breaking down of people’s lives.’ He cites recent Salvation Army research, predicated on interviews of 16,000 Australians, that identifies homelessness, mental health and financial hardship as our most significant issues.

What we’re witnessing isn’t so much a homelessness crisis, as a crisis of imagination. Hiding or relocating a problem has proven an easier response than solving it. And as the housing crisis deepens, the cost-of-living rises, and the mental health burden grows, cities around the world face the same choice: hide the suffering of its most vulnerable people, or meet that suffering with empathy and dignity?

In a city that sees people without homes not as citizens to be included, but nuisances to be hidden from tourists, Brendan is regularly outspoken about providing rough sleepers with greater access to housing and the necessary supports ‘that they need to get them back on their feet’. That call is still relevant. Still timely. But it’s a call that too often falls on deaf, angry ears.

Cities, at their best, are shared fictions that exist because we agree to live beside one another, not in spite of one another. But the moment we start insisting that our cities hide or punish suffering instead of responding to it, we forget what makes society just. A city that barricades itself against its most vulnerable residents may feel secure for a time, but in the end, the danger isn’t the outsiders it locks out, but the capacity for decency that it refuses to let back in.

Barry Gittins is a Melbourne writer.